The Rule of M - A Better Cure for Rectal Endometriosis

There has been a gaping hole at the bottom of how we treat rectal endometriosis. Today, we fix that hole.

Today’s issue wouldn’t have been possible without the wealth of knowledge and insights that we inherited from Dr. Sanjay Patel and Dr. Lakshman Khiria

Endometriosis really changed what a gynaecologist’s OT looked like. Go back 15 years in a time machine and you will only find a gynec with their laparoscope, happily removing the uterus, or fiddling with a hysteroscope. Today they're not alone.

With its multi-organ involvement and deep infiltrating nature, endometriosis wasn’t a jolly old gynaecologist’s solo gig anymore. They had to look towards urologists and gastrointestinal surgeons to solve the problem of ureteric and colonic involvements. Without that, there was no symptomatic relief.

The OT, earlier a sanctuary for serene crafts, was now a cauldron of opinions. The number of operative procedures on the colon spiked, and with it, spiked the number of resection and anastomosis procedures, making way for a grim adversary - LARS or the Lower Anterior Resection Syndrome.

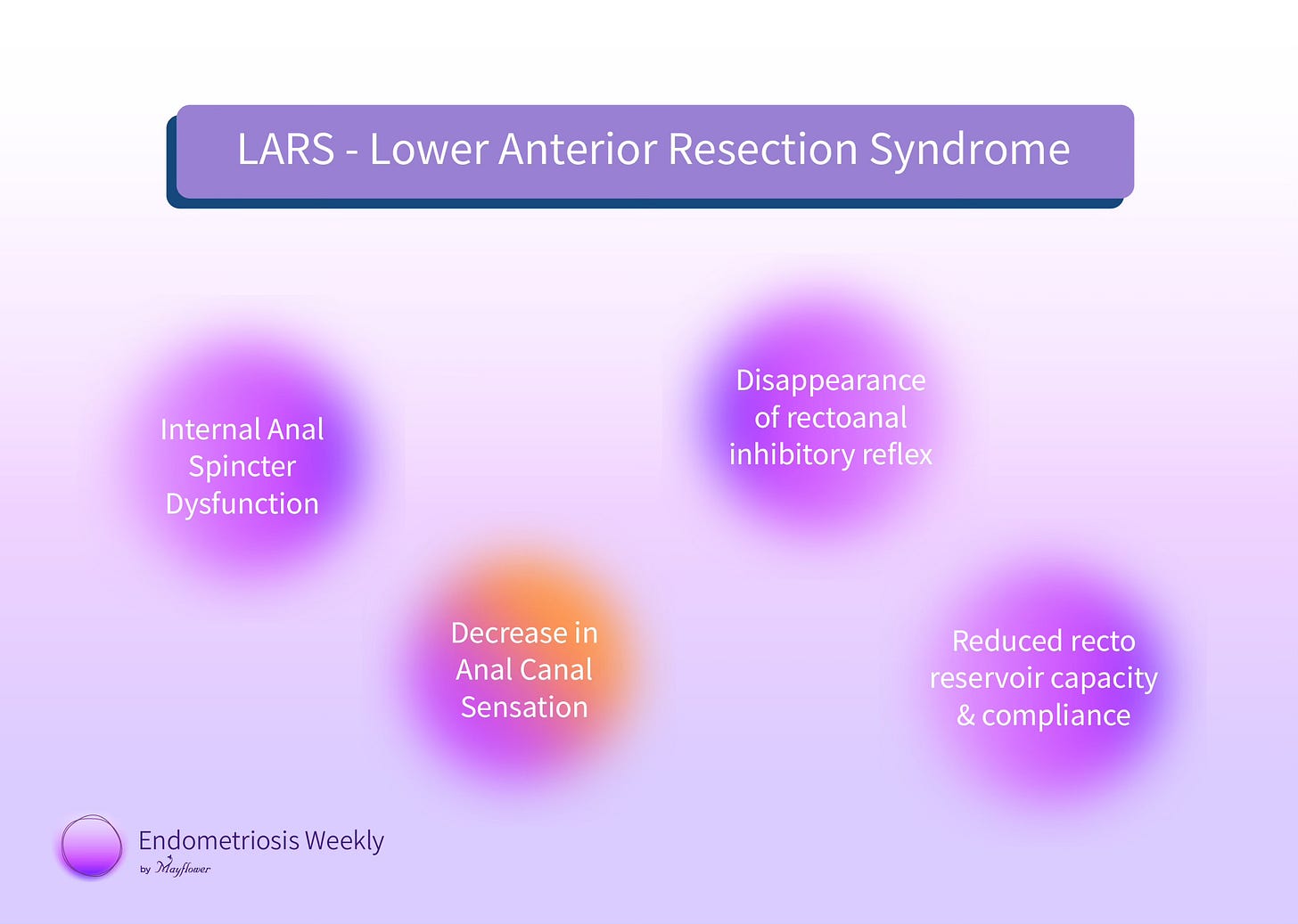

The LAR syndrome is likely multifactorial and several proposed pathophysiological mechanisms for LARS include internal anal sphincter dysfunction, a decrease in anal canal sensation, disappearance of recto-anal inhibitory reflex, and a reduction in recto reservoir capacity and compliance. As a result, patients suffer from grave post-op recovery periods and suffer a great deal more emotionally.

Ultimately, we fail as surgeons when we can’t deliver to them a life they look forward to living.

Something had to change.

We needed to come up with a better way to cure the disease, for the sake of our patients, and for the sake of thousands across the world who might undergo this procedure.

So we went back to the drawing board.

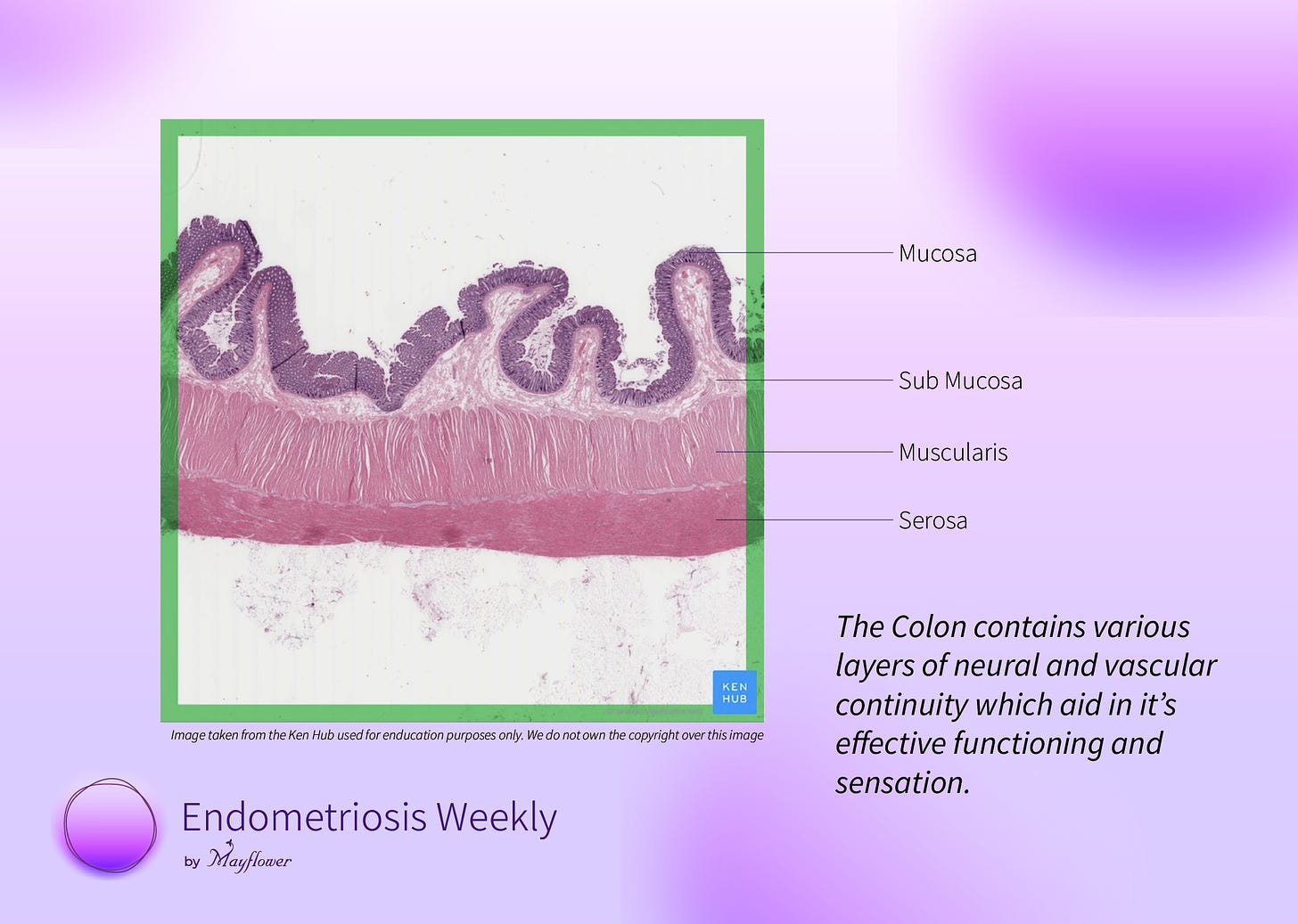

The picture became clear. LARS and long recovery were occurring primarily because of neuro-vascular discontinuity as a result of the procedure. If we could somehow avoid resection, but still deliver on its benefits, the biggest of which is total disease removal, we would have achieved a great deal for our patients.

So instead of dissecting the full circumference of the colon, we need only dissect as much as needed, with minimal disturbance to

The neuromuscular continuity of the colon

The luminal diameter available for stool to pass

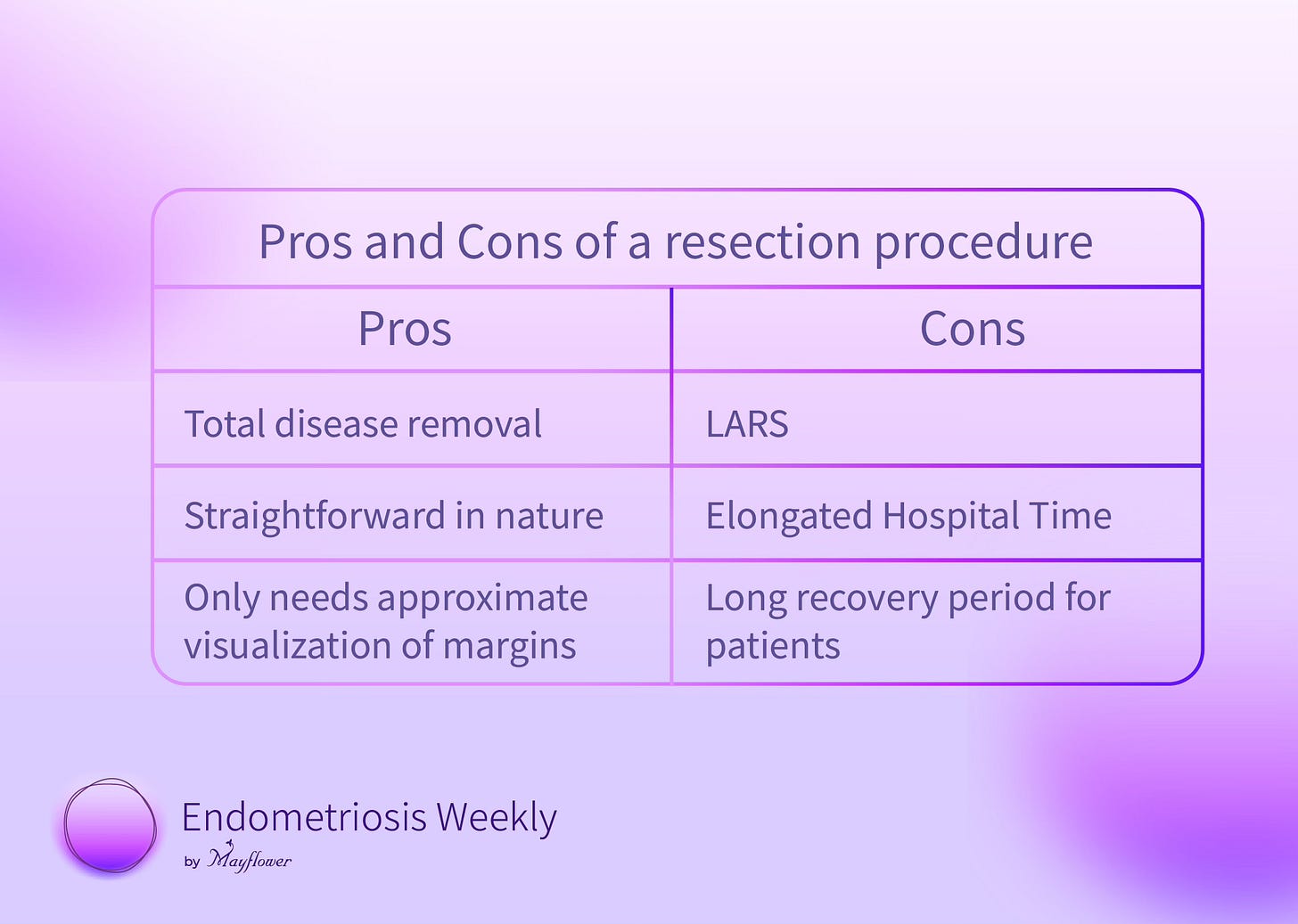

The first principles at play here are surprisingly simple. If we avoid R&A, we avoid complete discontinuity. Even if we need to suture it back after an anterior discoid resection, it will adapt to the new lumen available. Given the circumferential involvement is limited.

Let’s break this down into different cases. One step at a time.

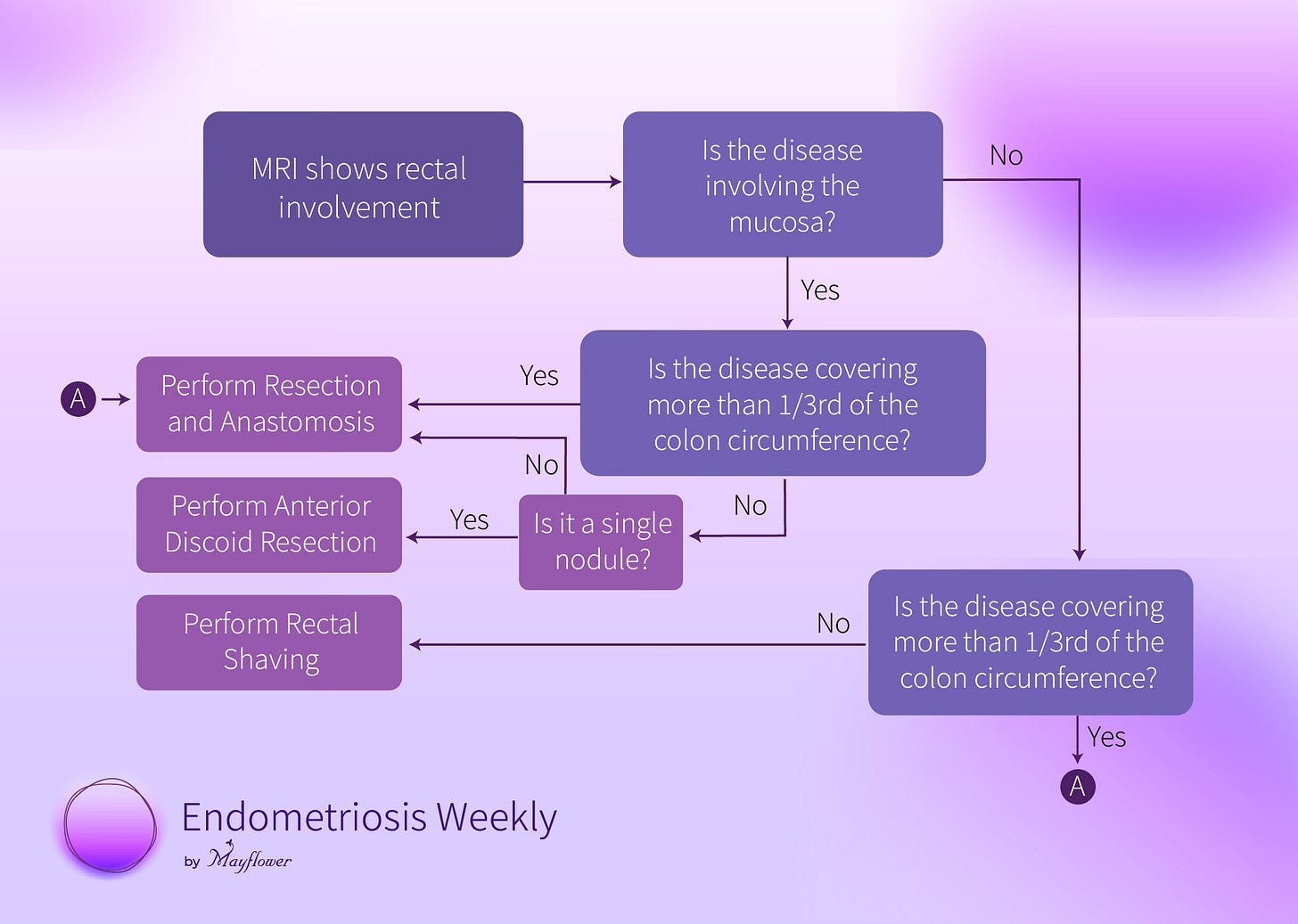

First, we have localized extra mucosal nodules. Meaning, that they cover less than a third of the circumference of the colon, and aren’t invading the mucosa of the colon.

That last bit, about not invading the mucosa, that’s important. The mucosa directly represents the available lumen of the colon and any invasion to it, means a dissection will reduce the finally available lumen at the point of repair.

Next, comes localized nodules (cover less than a third of the circumference of the colon) that are invading the mucosa. This requires that we excise the full nodule. If it’s a single nodule, this can be achieved via an anterior disc excision. Here the lumen directly decreases but the flexibility of the colon makes things easy.

If we have multiple nodules, resection is the only way.

Finally comes the case where circumferential involvement is more than a third of the way around the colon. In this case, regardless of whether the mucosa is involved or not, only shaving off the nodule and suturing it back will cause significant bunching up of the internal lumen effectively reducing the net available area and crossing the threshold of what the colon can compensate for. Which is why we prefer a resection and anastomosis procedure.

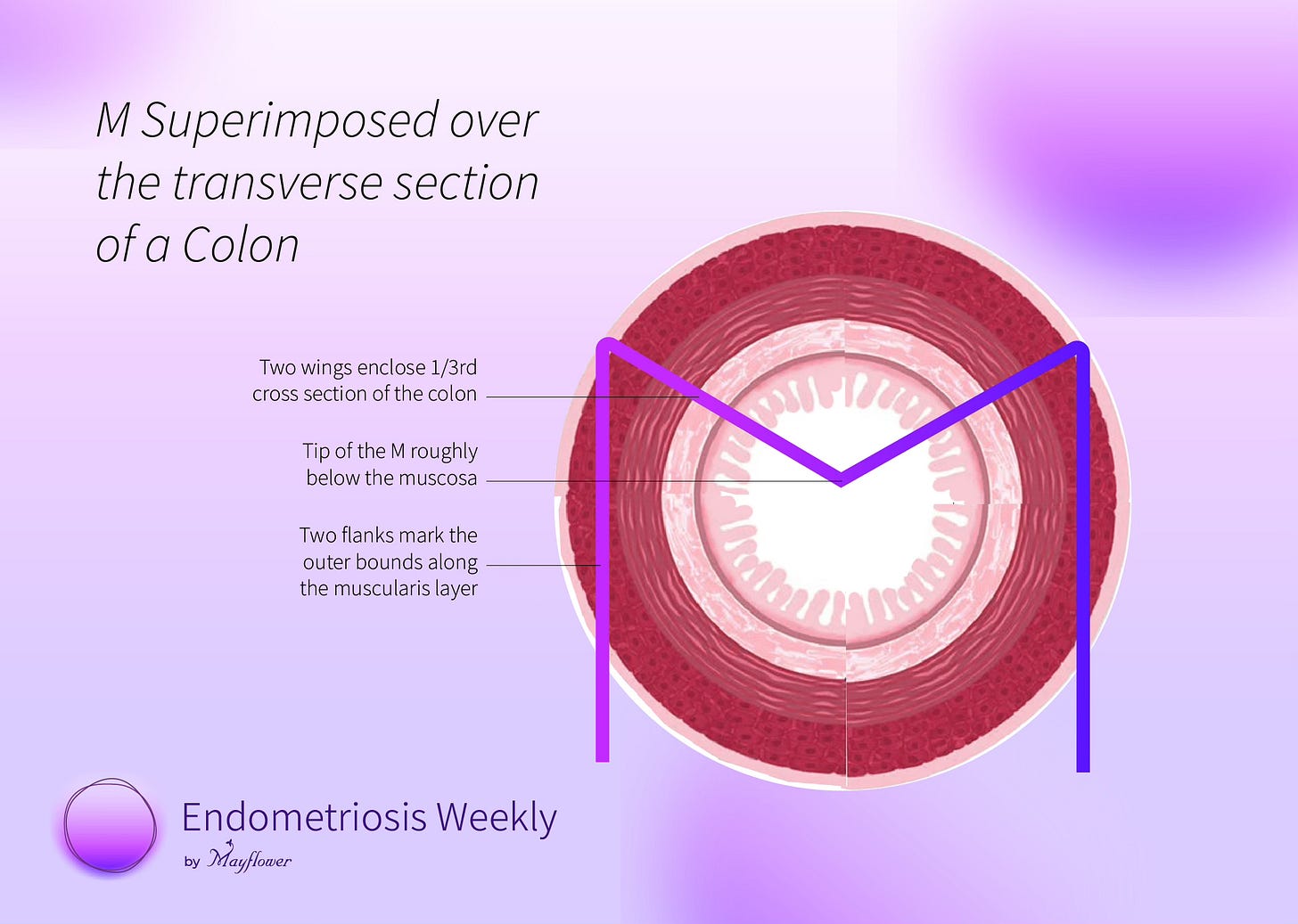

To make this simple, we made a visual guide that we call The Rule of M

Imagine the cross-section of the colon, and superimpose an M on it.

The two legs of the M mark the outer bounds of the colon while the two wings of M mark between them a 1/3rd section of the colon, with the tip of the M falling roughly where mucosa ends.

If the nodule(s) fit within the two wings of M and isn’t invading the mucosa, perform rectal shaving. This will cause minimum damage to the continuity of the colon and protect nearly the entirety of its luminal area previously available.

If the nodule is single, fits within the two wings of the M, but is touching the tip (invading the mucosa) it’s a case for anterior discoid resection (ADR). If they’re multiple, choose resection and anastomosis (R&A).

In case the nodule crosses over the two wings of the M, go for R&A

Note that the length of the colon involved is not at all of concern here. At Mayflower, we’ve shaved significant lengths of the colon with this thumb rule seeing no change in patient outcome and pain relief or hospital time post-surgery.

For the engineer inside you, here’s a flow chart.

It’s that simple.

But now comes the hard part. The toughest of the three choices (shaving, ADR, and R&A) is when we pick shaving a nodule over R&A.

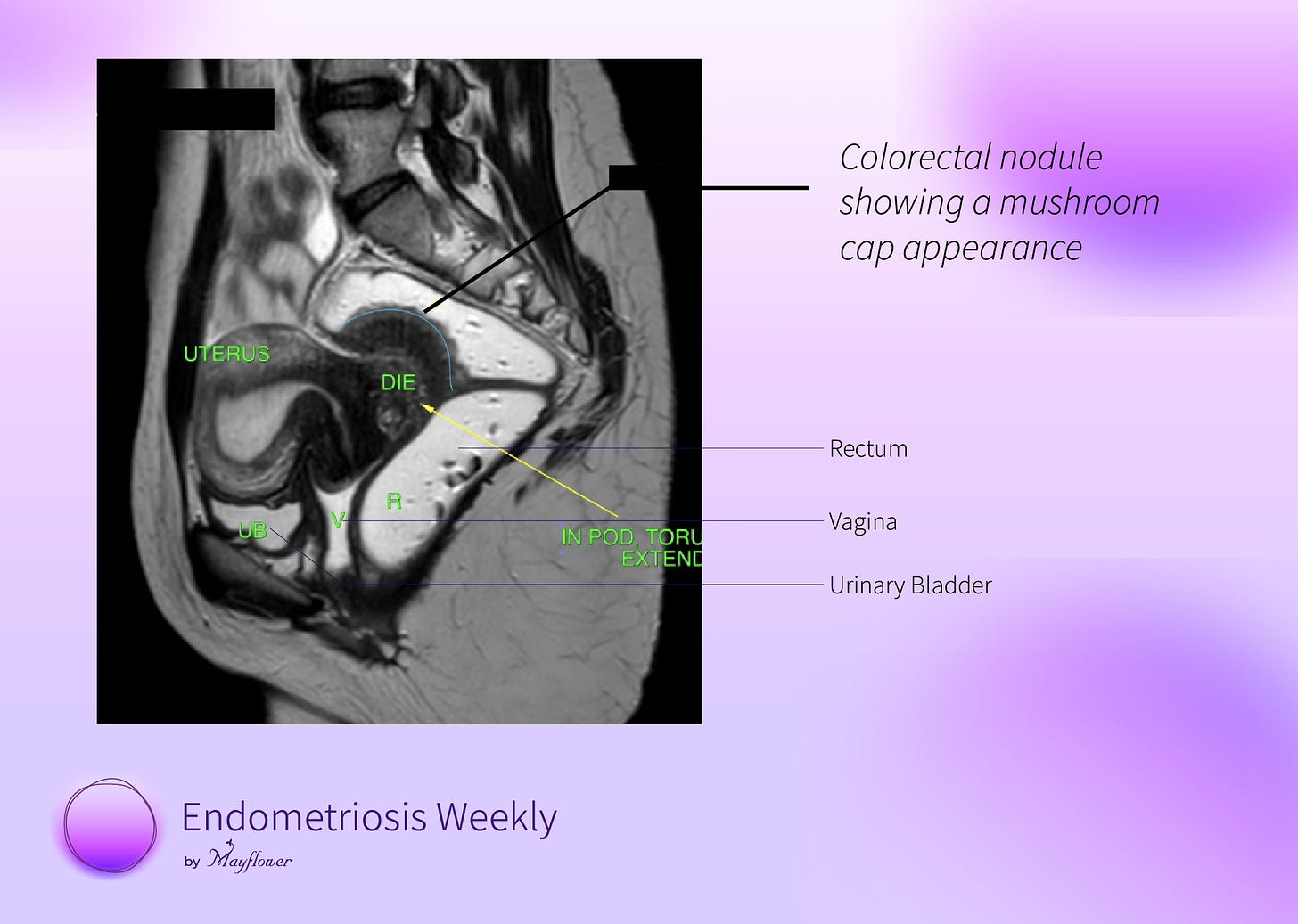

It gets harder when the nodule is present along the recto-vaginal fascia and infiltrating both into the uterus and the colon. On an MRI, this shows as a mushroom cap.

The best way we know so far to excise it is as follows

Step 1: Split the nodule

Split it along the recto-vaginal plane staying as flush to the fat of the colon as possible. This will send a large part of the nodule towards the uterus and you know how to deal with that.

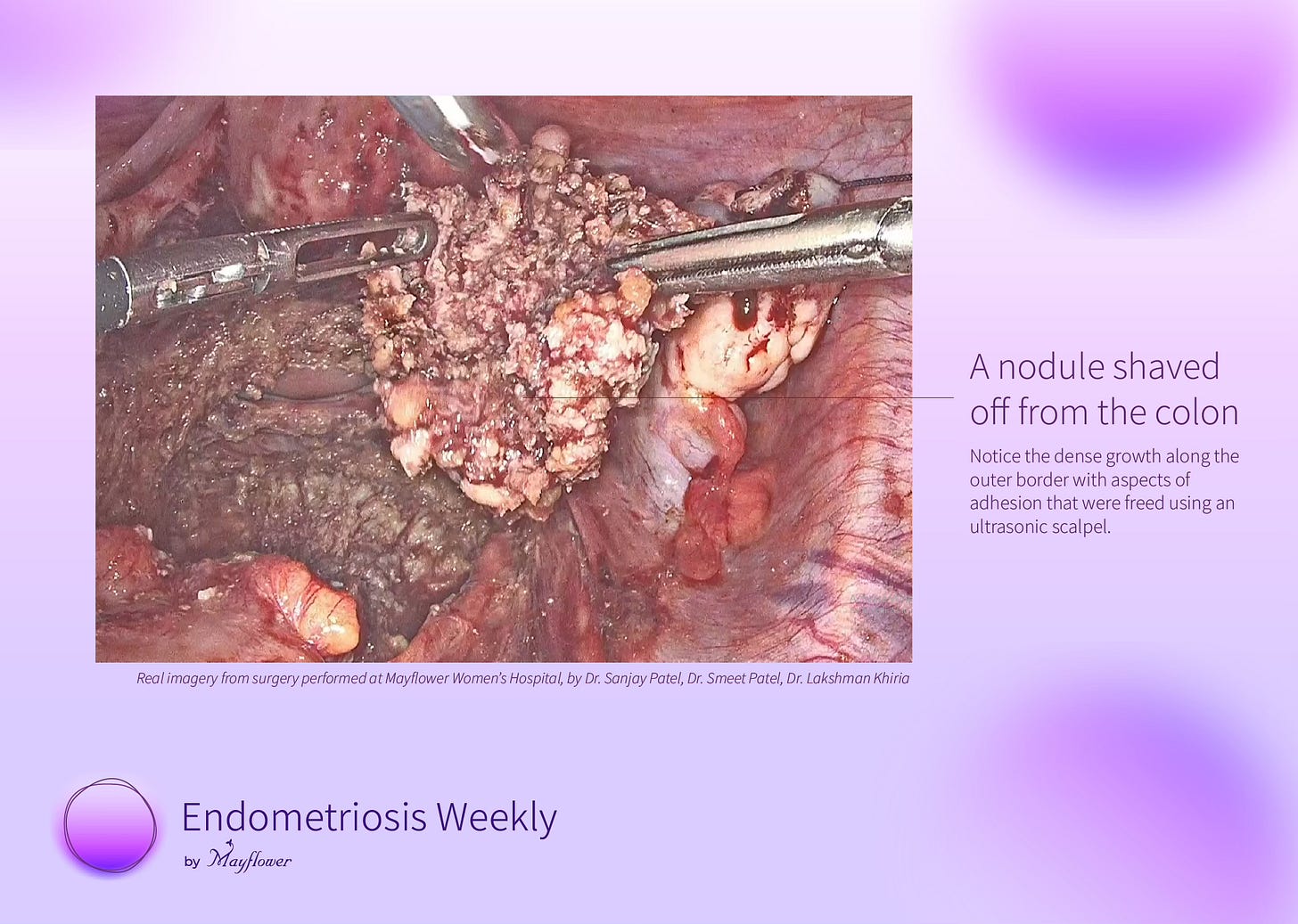

Step 2: Denude the fat

Slowly, but surely, bit by bit, denude the fat from the nodule, giving you a clear margin of its actual existence. Being careful, slow, and precise is more important than anything else in this step. At the end, you will have a clean outline of the nodule.

Step 3: Pop it up!

The nodule is imparting compressive stress to the colon. You can only visualise the top of it and major pathology lies beneath the surface but if you want to excise it without perforating the colon, proceed slowly, use the tip of your ultrasonic scalpel snip gently on different points of the surface and this will slowly pop the nodule out.

Step 4: Shave it off!

With the tense adhesions out of the way, careful shaving towards the invasive part of the nodule will free it from the colon and you will have with you a beautiful, single block, excised nodule.

We have this cool video over on YouTube where we explore all three methods of disease exision in great detail. Give it a watch!

Over the last five years, this simple thumb rule has helped us create customized surgical approaches for thousands of patients and given us the confidence to pick the more conservative approach saving millions of rupees, hundreds of admission days, and most importantly giving our patients a life they once had, physically and emotionally.

Picking the conservative approach pushes the boundary of surgical skills and forces us to find better ways of restoring the anatomy instead of picking a route where the disease gets removed, but the pain remains.

A surgery starts long before the cautery first meets the skin, and lasts long after the last suture has dissolved.

As doctors, our job isn’t just to eradicate disease, but to restore life, often in places where it is least likely. That’s what makes us alive.

Thank you for making it to the end of this edition of Endometriosis Weekly. We hope it was worth your time. Please make sure you leave feedback in the comments below and forward this to your friends who might also enjoy it.

Special thanks to Dr. Baishali Jain for helping edit this version of EW