Hey doc!

At a gathering of true experts, you would be called a liar, and an imposter, if you told someone peritoneal involvement isn’t a common occurrence in most of the cases you see. It’s almost a given. And yet, dealing with the disease over this connective and complex tissue is challenging.

In today’s edition we break down what about the peritoneum makes it so complex, and how we can surgically deal with it. Let’s dive right in.

Before we begin, here’s a brief reminder that the Endometriosis India Survey is LIVE right now. If you haven’t already, please fill it up soon and help us build the India’s largest shared knowledge base of a surgeon’s approach to endometriosis

Thanks for fill it! Now, on to our edition for this week.

If endo-cells were a bunch of hitchhikers trying to get around the pelvis, the peritoneum would be their Uber Pool.

The Peritoneum: Basically A Bubble Wrap Around Your Organs

Imagine your insides are all snuggled up in a giant sheet of cling film. That’s your peritoneum. It lines the abdominal cavity and wraps around pelvic organs like a very dedicated spa robe.

Now, when endometriosis cells get in there (the uninvited party guests), this stretchy membrane becomes their all-access pass to sneak around — to the ovaries, bladder, ligaments, even the diaphragm if they’re feeling ambitious. They don’t need a map; the peritoneum is the map.

Endo Cells Have Sticky Little Superpowers

Once these endo cells land on the peritoneum, they don’t just chill. Oh no. They stick, burrow, and build their own little mounds. Stubborn, invasive, and armed with enzymes that say, “Let me just dig in a little deeper.”

They also call for reinforcements: new blood vessels, inflammation, and chaos. Once they implant, they can:

Induce inflammation

Stimulate angiogenesis (new blood vessel formation)

Release enzymes that help them invade deeper tissues

This makes it easier for them to move along the peritoneal tissue, like a spreading vine using the membrane’s surface.

Peritoneal Inclusions are Sneaky

It isn’t rare to never spot endometrial involvement of the peritoneum on an MRI. Peritoneal endometriosis is often made up of tiny, flat implants that are:

Just a few millimeters wide

Not raised

Not always pigmented

Sometimes buried under the surface (called subperitoneal)

On MRI? That’s basically trying to spot a freckle in the dark. If it doesn’t cause distortion, bleeding, or inflammation — it’s likely invisible.

MRI detects contrast — the difference between how tissues respond to magnetic fields. Fat? Easy. Blood? Sure. Fluid? Of course. But peritoneal lesions? They’re often:

Low in volume

Low in contrast

Similar in signal to surrounding tissues

So even if they’re there, they don’t stand out. They're like the background singers of pelvic disease — doing damage, but not hogging the spotlight.

Only the Drama Queens Show Up. When the disease has spread using this peritoneal tissue highway, it can occur at various places as

Fibrosis

Inflammation

Bleeding

Tethering or puckering of nearby tissue

That’s when they’re more likely to show up on MRI. Until that happens, they’re just lurking under the radar.

Imaging Isn’t Magic

Peritoneal endometriosis is a microscopic disease before it becomes a surgical one. Sometimes, the only way to actually see it is to go in with a laparoscope, take a look around, and biopsy what looks suspicious.

MRI is a fantastic tool — but it’s not a mind reader, and it’s not a microscope.

Act II: The Proliferation

Let’s say a tiny bit of endometrial tissue ends up on the peritoneum — not where it’s supposed to be, but hey, it’s still "normal" tissue, just in the wrong neighborhood.

Now, like clockwork, every cycle it responds to hormones.

It grows.

It sheds.

It bleeds.

But there’s a problem: there’s no exit door here. So the body goes,

“Umm, what’s this doing here?”

It tries to contain it — not kill it (because it doesn’t look dangerous). More like building a polite fence around an unwanted guest.

Next cycle? Same drama.

More growth. More bleeding. More inflammation.

Over time, that spot gets sticky. Scarred. Fibrotic.

What started as a harmless hitchhiker turns into a full-blown troublemaker — spreading pain, pulling tissues together, and messing with everything around it.

And that’s the silent chaos of peritoneal endometriosis.

We know the peritoneum isn’t just sitting there like plastic wrap. It’s a dynamic, living membrane. Think back to those biology classes — remember the osmosis experiments with the leaky potato or the egg-in-vinegar situation? Yeah, that kind of membrane.

The peritoneum absorbs, filters, exchanges — it's not just a passive wall, it's more like a smart bouncer at a club. It decides what gets in, what stays out, and sometimes, who gets stuck in a corner (hello, endometriosis cells).

So when those endometrial-like cells land on it, it’s not a blank stage — it’s an interactive surface. It responds, reacts, even tries to wall off or accommodate the intrusion. This constant back-and-forth? It plays a huge role in how endometriosis evolves.

The peritoneum isn’t just scenery. It’s in the story. Every cycle.

And that’s exactly why we will now take a look at 4 very specific, frequently affected, and tricky to manage, regions of the peritoneum, and understand them a little better.

Parietal Peritoneum Of The Right Paracolic Gutter

This area lies within the peritoneal cavity — along the right side of the abdomen, right next to the ascending colon and close to the appendix.

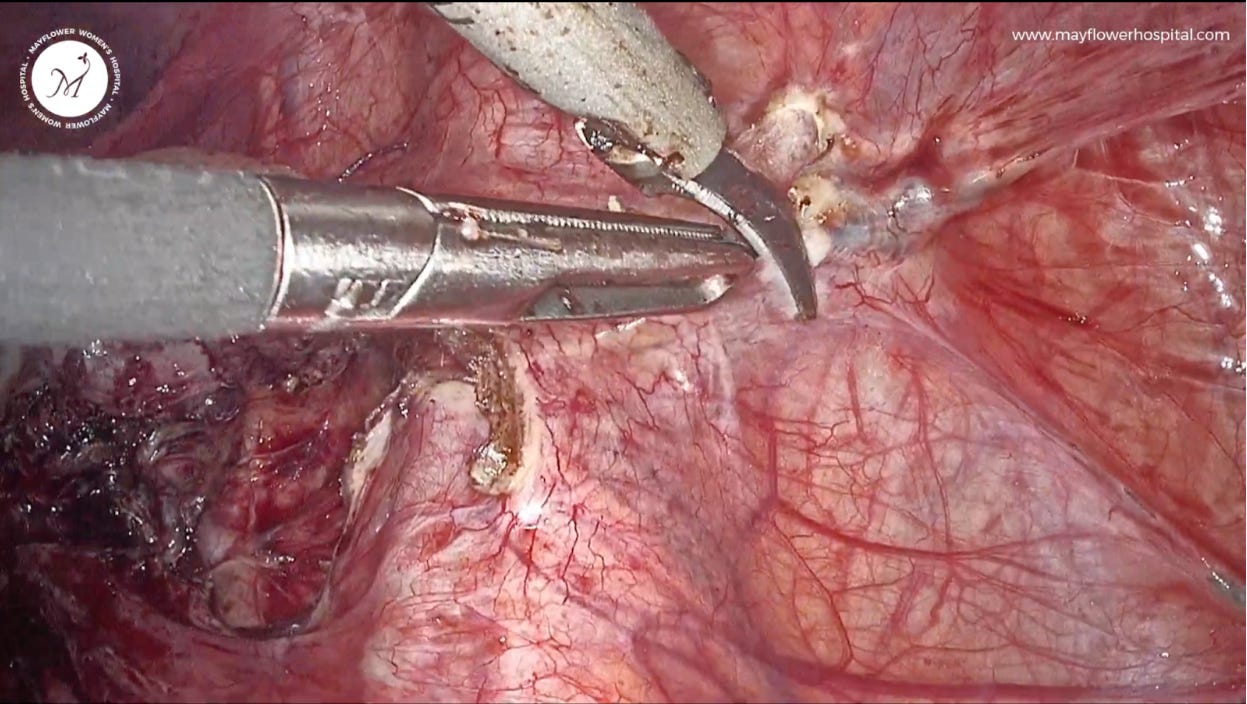

Dissection: Here, we gently lift the loose peritoneal fold, make a precise nick using the ultrasonic scalpel, and then — fiber by fiber — carefully excise the diseased tissue. It’s meticulous work, but that’s exactly what this disease demands.

Peritoneum Of The Vesico-Uterine Pouch

This section of the peritoneum is part of the vesico-uterine pouch — where it reflects from the front of the uterus onto the dome of the bladder.

Dissection: We make a careful nick just beside the endometriotic plaque, at a spot of healthy peritoneum. Then, using a fiber-by-fiber dissection technique, we gently work our way through — ensuring the bladder’s serosal surface stays completely intact. Precision here is everything.

The Lateral Peritoneal Triangle

The LPT can be anatomically landmarked or bounded by the following structures along different directions

Round ligament anteriorly

External iliac vessels posteriorly

Infundibulo-pelvic-ligament superiorly

And the obliterated umbilical ligament medially

This is also a critical zone for:

Opening into the retro-peritoneum

Accessing lymph nodes within the pelvis

Dissection of deep infiltrating endometriosis

A route to avoiding injury to the inferior epigastric and external iliac vessels

The Hepatorenal and Perinephric Region

The right upper retroperitoneum and the posterior subhepatic space are key anatomical zones — whether you’re in general surgery, gyne surgery, trauma evaluation, or working through a retroperitoneal dissection. Knowing the layered structure here is essential, especially when navigating two important areas: the hepatorenal recess (Morison’s pouch)and the perinephric space.

Hepatorenal Recess (Morison’s Pouch)

This is a potential space tucked between the underside of the liver’s right lobe and the front of the right kidney. Small space, big clinical significance — especially in fluid collections.

Perinephric Space

This is the fat-padded zone that surrounds the kidney and adrenal gland — a cushion-like compartment that often becomes your surgical landmark (and sometimes your challenge).

Dissection in each of these spaces involves the same set of steps. Anatomical awareness, landmarking, and distortion understanding play a key and pivotal role in defining the quality of the surgery.

The simple thumb rule is to always lift-where-it-is free, and cut the peritoneum around the disease with only as much margin as you really need.

That’s it from us this week. We will see you in the next one.