Nuclear Surgery? Lessons on how to avoid Resection & Anastomosis

And when you can't anymore, how to do it right.

Unless you were in a comma last week, you couldn’t have missed just how absolutely close two nuclear powers came to a full fledged war. We received a very direct and certain nuclear threat. If you follow the conspiracy trail, you will reach a very juicy conclusion that we even destroyed some of the enemy’s nuclear arsenal and caused them an earthquake.

We will never really know how much truth there is to these claims. But for a very short period, we felt that sinking feeling in our hearts that things might escalate much faster than we imagined. And we came face to face with the idea of what using a “Nuclear Option” could feel like.

Take a moment and think about this carefully. The nuclear option as is common said has some characteristics

It is certain and decisive. You get the outcome you’re looking for

It is the end of a lot of things, including the war

It leaves several unwanted after effects for the victims

Think of this now in terms of surgery. Every patient you see can be treated using some nuclear option parallel. You can remove the mayomectomy, ooferectomy, and more specifically for today’s edition, a resection and anastomosis surgery.

Colonic involvement of endometriosis is a serious and difficult situation. If you don't deal with it, it can be very painful, very harassing, and eventually fatal. But when you choose to deal with it, going for the nuclear option of resection and anastomosis needs to be a careful and considered choice. One you only take when everything else has been ruled out.

Resection = Nuclear Option

It is certain and decisive - the disease and any alteration of the anatomy is OUT

It is the end of a lot of things - resection puts a stop to the disease but also to a lot of the patient’s regular life, at least for some time.

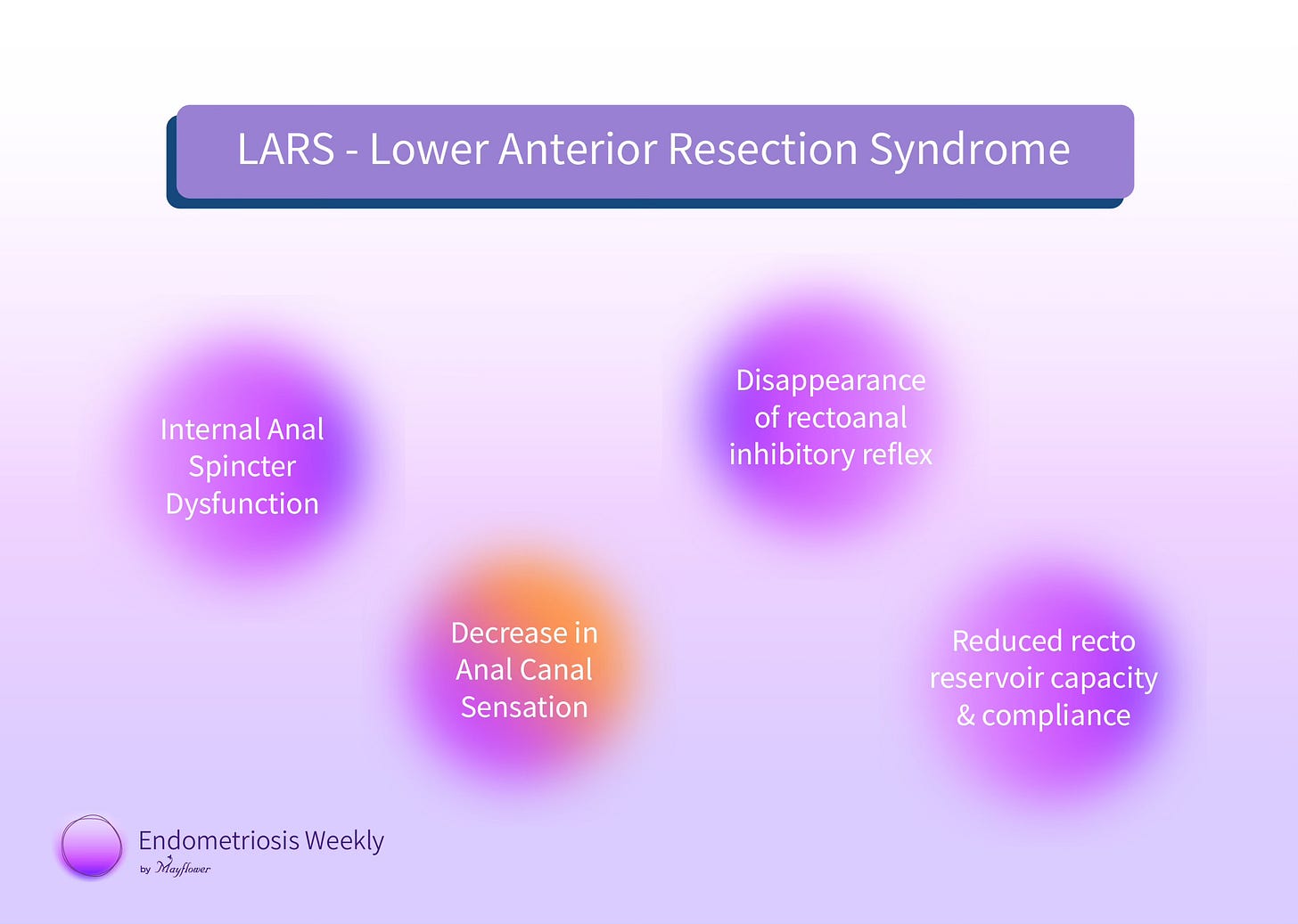

It leaves several unwanted after effects - LARS being the most dangerous one

LARS - Lower Anterior Resection Syndrome

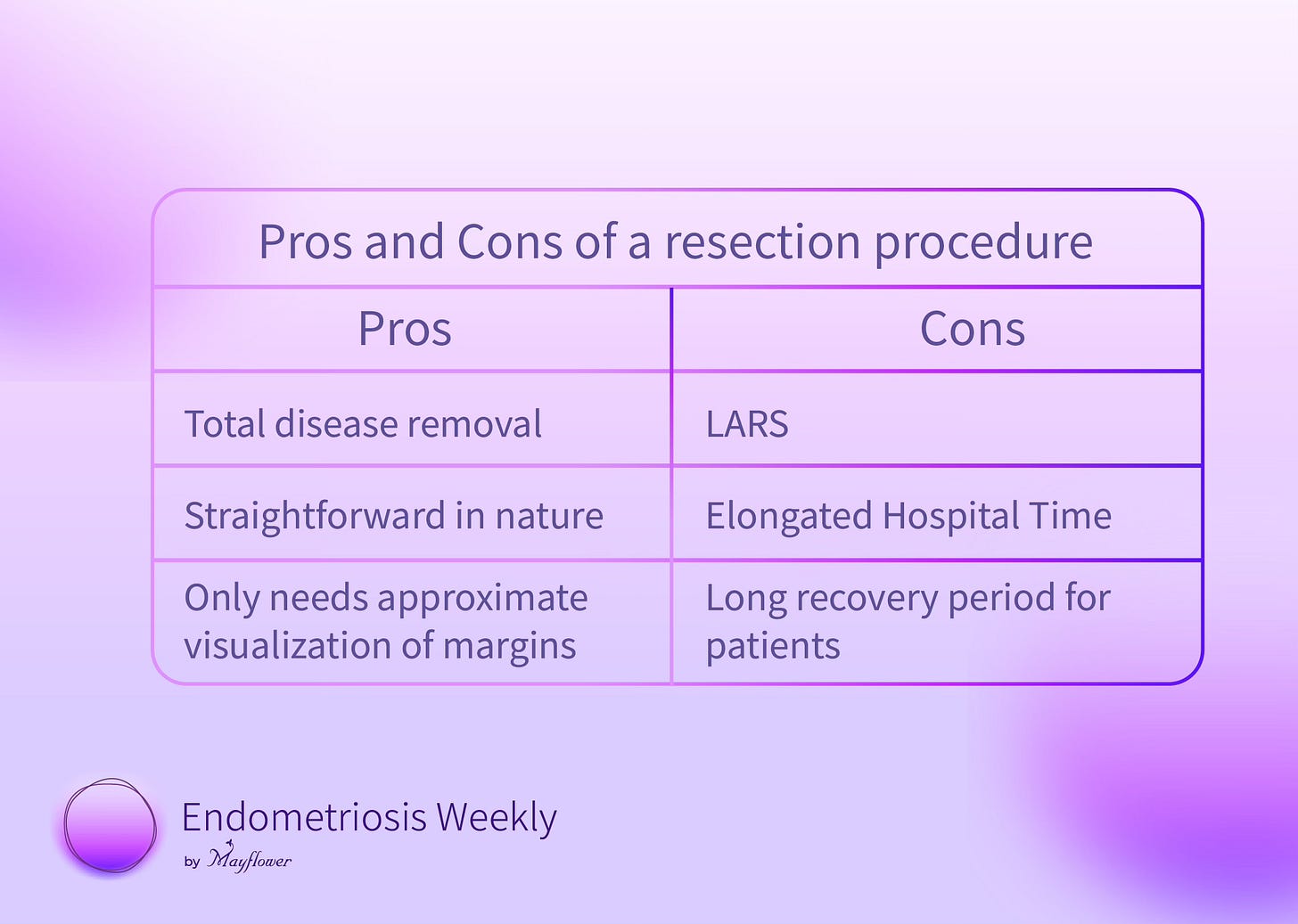

The pros and cons of the procedure are now clear to us

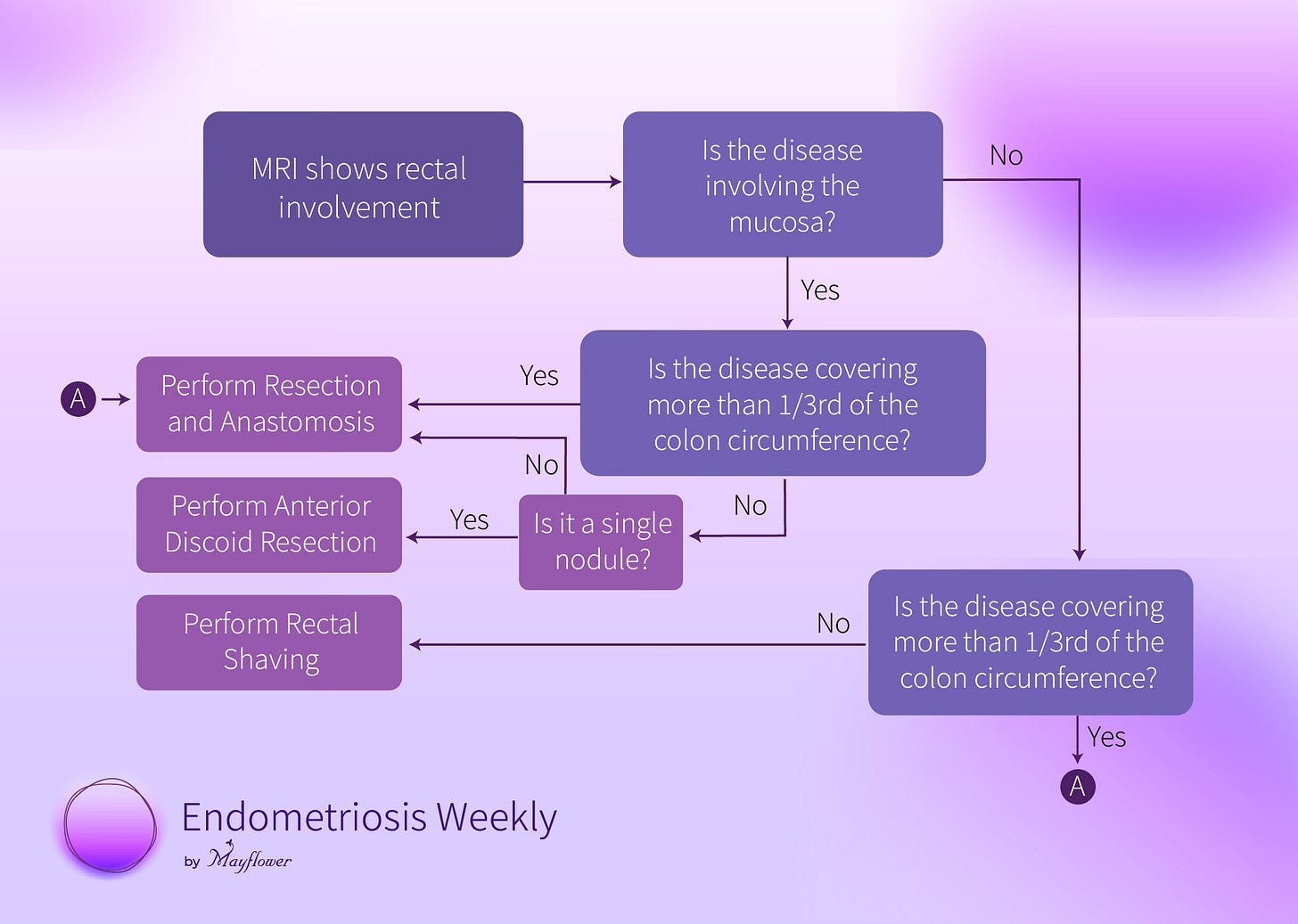

The Rule of M is a framework that helps us decide, which case to triage for resection and which to deal with differently. We explained it in a flow chart some time back

We’ve seen a lot of cases that could’ve been dealt with discoid or rectal shaving move to resection and anastomosis because of a variety of reasons. While getting into them is tough, we’ve seen this method help us the most in making a solid choice.

However, every once in a while when you do have to take the nuclear option, it’s important to do it right.

In essence, Resection and Anastomosis is simple. We delineate the entire involved section of the colon with some margin; then with the help of a circular stapler and linear stapler, resect that segment, and simultaneously reconnect the two new ends.

Sounds simple. Except that as we all know, the colon isn’t a piece of plumbing. Before we make any plans, one way to the other, we take a look at the MRI.

Take this example for instance. You can see circumferential involvement of more than one third of the colon. In this case, performing an anterior discoid resection or shaving off the shallow nodules and then suturing would constrict the colon which is the sole reason we carry a resection and anastomosis.

Also keep in mind, and counsel the patient well that R&A is an anatomy altering surgery. It involves irreparable neurological, vascular, and organ damage and it must be well understood that the procedure has a potential of doing more wrong than good to the quality of life of a patient. It stretches the colon, creates tension, and alienates the bottom length of the colon thereby prolonging recovery time. And when closer to the sphincter muscle it can cause a lot more havoc in daily life. That being said, in some cases, as strictly qualified by our rule, it remains the only procedure that can help restore some semblance of a regular life for the patient.

With that, let’s look at the surgical steps

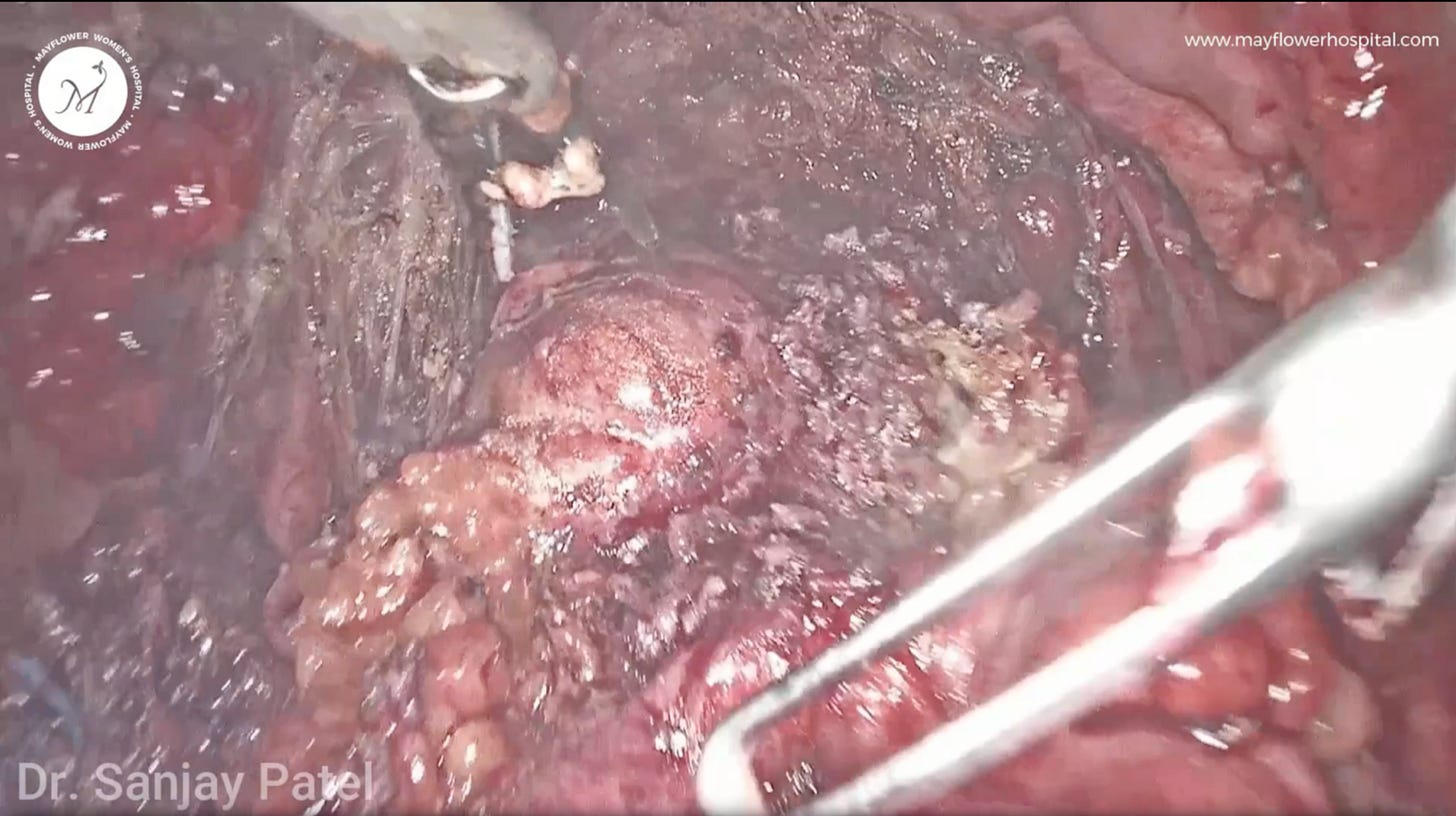

We notice in this case that the disease has heavily infiltrated into a section of the colon. In cases like these we prefer to do a bowel resection because of the involvement of multiple nodules and circumferential involvement is more than one third of the colon.

Mobilizing the colon in such cases is a very important step as it sets the base for how easy and clean this procedure eventually will be. The anastomosis we are about to conduct needs to be tension free. The colon must be able to move freely as we’re about to remove a segment and extend the organ’s reach.

To begin, we enter the holy plain and free the entire colon from the sacral promontory to the pelvic floor between the 2 layers of the endopelvic fascia.

These are the two layers of the holy plain and we dissect them further to mobilize the colon. Dissection of the bowel from the meso-rectum and meso-colon is performed in contact with the dorsal wall of the recto-sigmoid junction, which helps to preserve the meso-rectum and meso-stigma, and safeguard the left and right hypogastric nerve, and the parasympathetic nerve plexus.

We sometimes place a gauss piece in order to lift the colon properly and then further carry out the dissection. Another important part of our practice is that we often sacrifice the inferior mesenteric vessels - to ensure proper mobility of the colon and also so that once cut, the colon is more relaxed and tension free.

We then dissect the inferior mesenteric artery and vein and block them using a liga-clip

In some cases we might encounter multiple vessels, two arteries and two veins, and so on. So we use multiple clips to make sure they are all properly sealed.

We’ve now achieved a very good mobility of the colon.

Our next step is to apply the circular stapler but first we must denucleate the region (for stapler application) from any fat globules around it. That’s because fat often compromises the integrity of the seal created by the stapler and you have chances of colonic leakage.

We again check the mobility of the colon and then proceed to set up the stapler.

Rather than placing an oblique cut, we prefer to apply the stapler transversely. In our experience this helps reduce chances of leakage down the line.

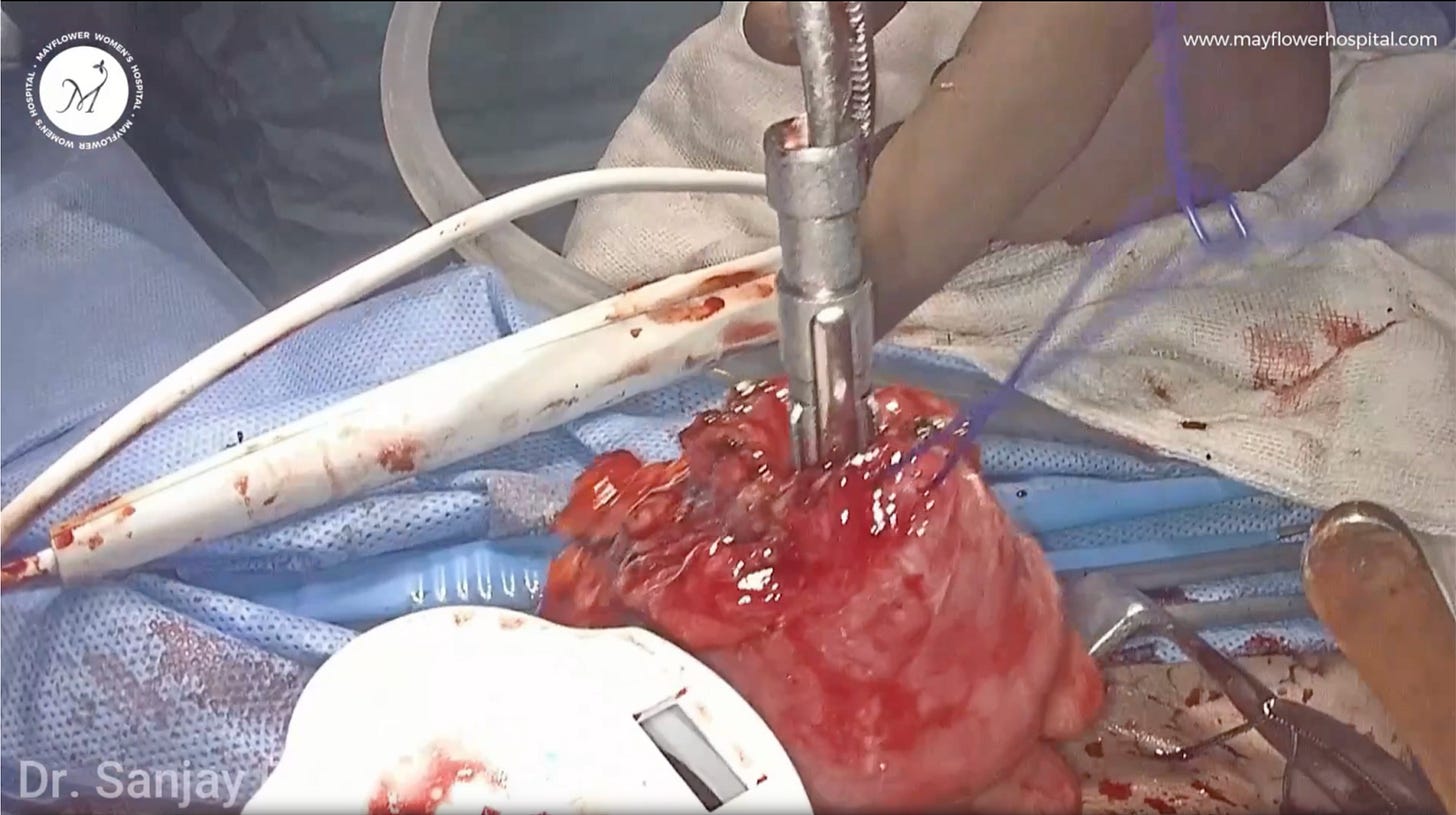

We then come out and put a transverse incision (about one inch) above the level of symphysis pubis, and through it we bring out the colon.

Ideally we prefer to use a wound protector ring here. We also try to remove all the fat surrounding it and then cut with a harmonic scalpel.

We then take stay stitches using prolene sutures in a continuous fashion and we fix the anvil in place and further remove any fat globules before pushing the colon back into the abdomen.

We then proceed to close the abdomen layer by layer while checking proper hemostasis.

Next, we push the plunger in from the anus, right below the line of the stapler and fire it.

Here we’re using a power stapler.

Two donuts recovered at the end of the procedure are indicative of our quality of surgery. Two proper donuts mean that our anastomosis was neat and complete.

Below is the resected specimen where you can see multiple nodules fully infiltrating into the colon .

That it! That’s the procedure.

Most endometriosis surgeries are based on simple mathematics. Fundamentals of surgery often seem like a practice you learn early on in your career but in our experience, it is the fundamentals that take long, and demand the most amount of willingness to learn.

Not just your memory but your consciousness must know them, as should your hands, and the tips of your fingers. More than surgical technique, procedures require surgical planning, part of it will happen pre-op, part of it intra-op. Strategising prior to entry, adapting strategy to what we encounter, and minimising collateral damage while removing diseased tissues ---- these are the things that come together to help our patients live a better life.

That’s it from us this week. We’ll see you in the next one.