In Surgery, fear is not your enemy. Denying fear is.

There is a moment in every complex endometriosis surgery where your hands start talking back to your brain. You know one thing to be true, but you start to feel the other way.

You’ve reviewed the MRI.

You’ve mapped the disease.

You’ve planned your ureterolysis, your rectal shaving, your nodule excision.

And then — as your instrument edges closer to a vessel, a nerve, or the bowel wall — something happens.

Your mind flickers.

Sometimes it’s fear. Sometimes it’s adrenaline posing as confidence. The difference between the two? That’s where great surgeons are made.

Any surgeon who tells you that they have never been scared doing surgery is either about to operate on you, or is lying. Fear is such a crucial part and parcel of becoming good at surgery that the only antidote known to it is practice.

But often, no amount of practice is enough. Nothing compares to when you first approach a tissue on a living patient who life and livelihood rests in your hands.

Dr. Atul Gawande writes

“Sometimes wrong; never in doubt.” This saying about surgeons, often intended derisively, struck me differently. To me, it seemed their strength. Every day, surgeons are faced with uncertainties. Fear, if unchecked, can be paralyzing—but neither can it be entirely laid aside. It must be managed, acknowledged, and used to inform our decisions, not hinder them. The balance between confidence and humility is delicate but essential.”

And it’s true. The only available antidote to fear is confidence. Which in itself can be poisonous.

Every time we dissect around the ureter, or lift nodules off the rectum, we’re walking a fine line. Not just anatomically — but mentally.

Confidence lets us take a decision when we need to. The cut is definite. It is clean.

Take it too far and overconfidence makes us ignore the need for help, or a pause.

Fear warns us of risk.

Hesitation, driven by fear, is where good surgeries go bad.

If you're too cautious, you delay, damage, or even abandon the procedure halfway.

If you're too bold, you clip a ureter or tear a vessel.

The right mindset is a tension — never fully relaxed, but never reckless

Real Moments in Surgery

Let’s talk specifics — the actual moments when this mental tightrope becomes most visible. These aren’t just technical decisions. They’re emotional decisions, split-second judgements where confidence and fear negotiate in real time.

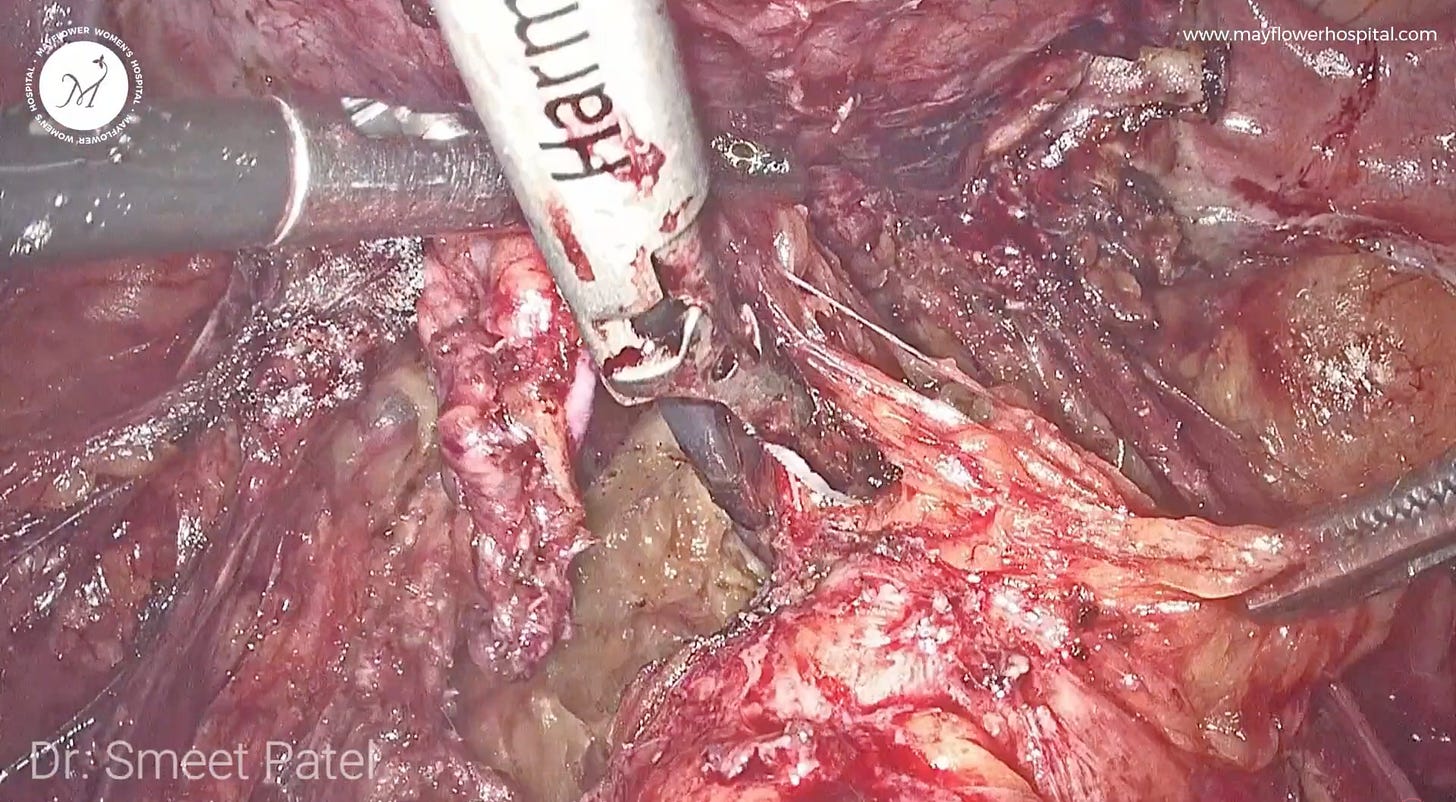

1. Shaving the rectum

There’s a reason so many surgeons hesitate here. DIE nodules on the rectum are often densely fibrotic and stuck in unpredictable planes. Confidence in this context means knowing where your dissection is safe — staying close to the disease, recognising avascular planes, and trusting your tactile feedback.

Overconfidence, though, whispers: “Just push through.” It assumes that this rectum is like the last five you did. That the disease is forgiving. That you’ll know if you're close to perforation. But bowel injuries don’t always announce themselves. They appear later, in angry post-op scans or rising CRPs.

And fear? That’s the voice that makes your hand pause unnecessarily, or back out of a nodule you should have removed. Hesitation — when prolonged — distorts your orientation, especially in a narrow pelvis. And sometimes, it robs the patient of the completeness of excision they came for.

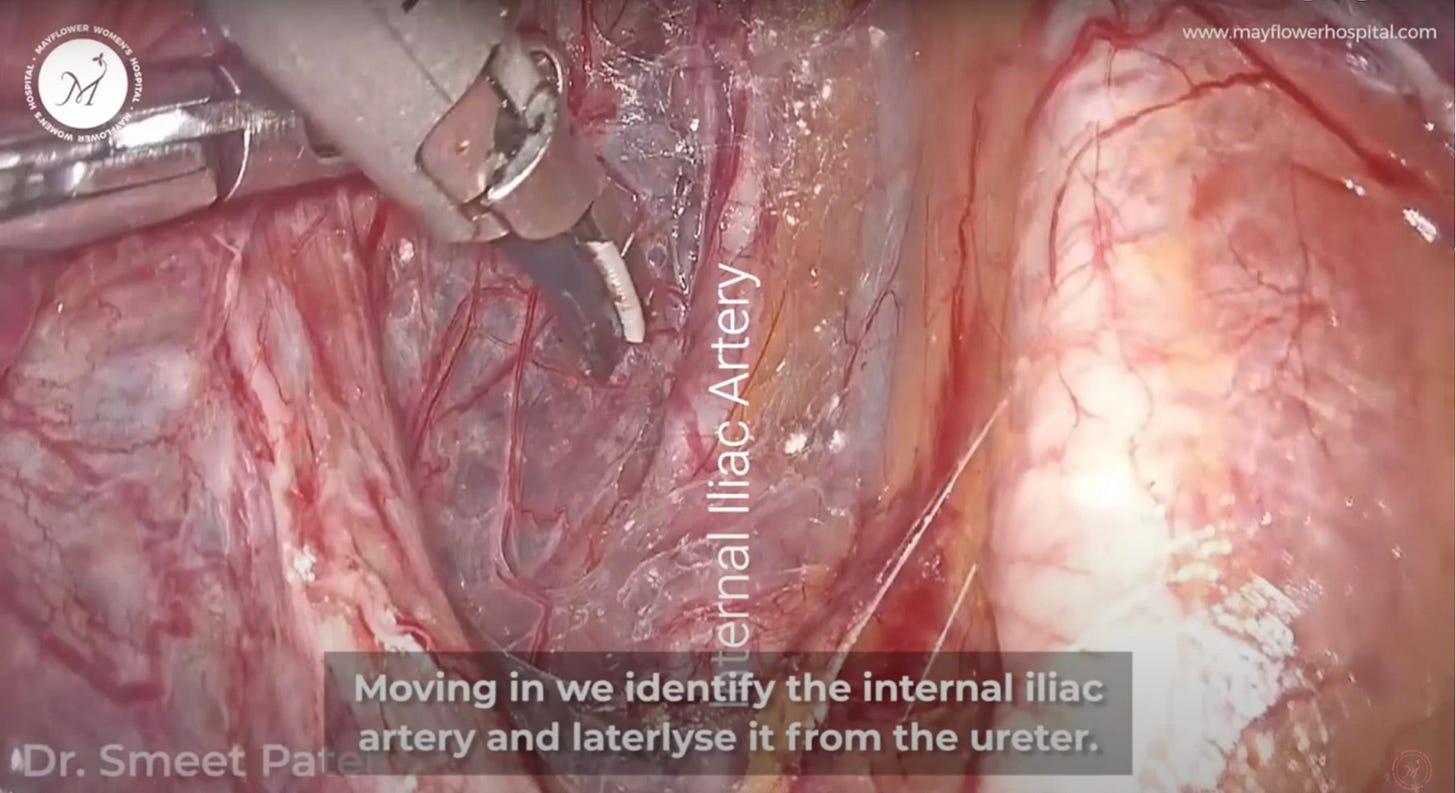

2. Ureterolysis

There’s nothing casual about ureterolysis in endometriosis. Especially when the ureter is tented up, encased, or displaced.

Confidence is early recognition — visualizing the ureter in the pelvic brim and tracing it centimeter by centimeter. It’s using the correct traction-countertraction. It’s being vigilant even when you're "sure" you’ve seen it.

Overconfidence is the assumption that because you saw it three centimeters ago, it must still be exactly where you left it. It leads to blind sweeps. It leads to thermal injuries — often unrecognized until post-op hydronephrosis or delayed leaks.

Fear can be useful here — it should slow you just enough to re-check your planes, adjust your angle. But let it go too far, and you’ll leave behind disease on the ureter, increasing the risk of recurrence or continued pain, sometimes even leading to structuring and kidney failure.

3. Dissecting near the uterine vessels

This is where overconfidence stops being a personality trait and becomes a risk factor.

The uterine vessels are not just "landmarks." They’re pressure points of potential disaster. You’ll often need to work nearthem — to access the parametrium or remove nodules close to the cervix or uterosacral ligaments.

Confidence here means appreciating vascular anatomy. It means knowing what you can coagulate, what you must preserve, and how to mobilise tissues without snapping into a bleeder.

Overconfidence shows up when you start thinking you can just “burn and go” — especially if you’re trying to save time, or the assistant’s retraction isn’t ideal. It’s the “I’ve done this before” syndrome — right until the bipolar slips, or the bleeder retracts and you lose your visual field.

Fear? If you let it dominate, you might avoid dissecting here altogether — compromising completeness. But when tempered, it forces you to use your best judgment: sharp dissection, clear visualisation, and readiness with a vascular clamp or clip if things go south.

The Dune Mindset

Dealing with hesitation, and giving yourself confidence isn’t a lonely challenge. Everyone who has ever been in a high stakes situation has to face it. The movie Dune offers a beautiful literary perspective to the problem

“I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration.”

– Frank Herbert, Dune

That line resonates in the OR more than most places. But we forget what comes next in the quote:

“I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past, I will turn the inner eye to see its path.”

In surgery, fear is not your enemy. Denying fear is.

Recognize it. Understand it. Use it. Then act — deliberately.

That’s it for this week. We’ll see you in the next one.