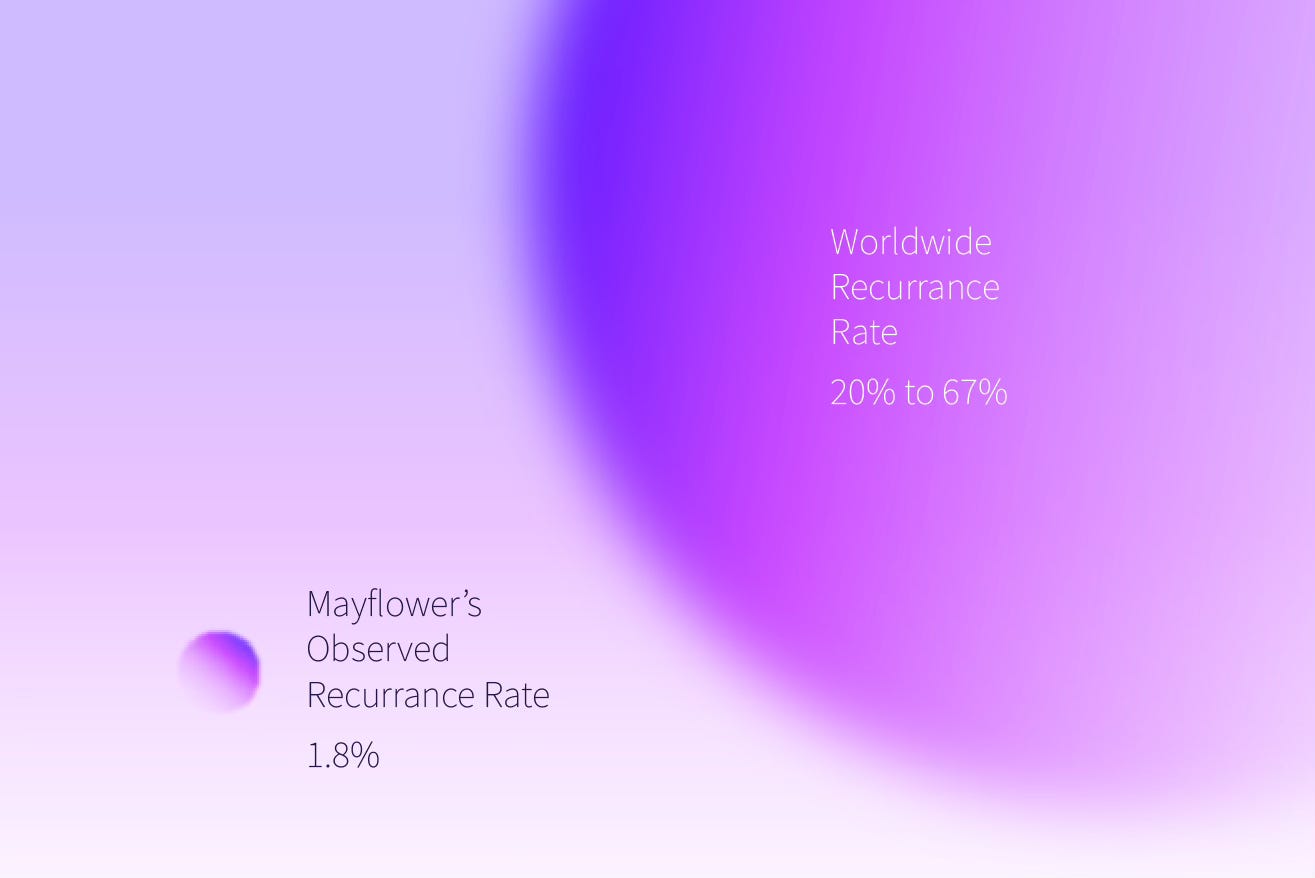

How Mayflower achieved a sub 2% recurrence rate with the Butterfly Technique

With a recurrence rate of less than 2% the Mayflower Butterfly Peritonectomy is a giant leap forward in surgery

Hey there! Good morning!

Today we’re talking about recurrance in endometriosis but before we begin, if this email appears clipped in your mailbox, please click on view full email to load it. Alright, let’s dive right in.

Did you complete your assignment? Asked the mother, the teacher, and the boss. Different people across your life have asked you the same question. Including your patients.

Did you?

Sometimes you were bold enough to say no. Other times, you weren’t done with it but wanted to be done with it and said yes. Left a few small nooks and crannies. Hoping no one would notice. Hoping what you did do was enough.

You move on in life but the assignments don’t stop.

Let’s dive deeper into what completing an assignment of endometriosis surgery really means, and how can we come as close to doing it as possible?

One of the toughest questions we face in the process of treating endometriosis is whether a surgery was complete.

Determining the answer to that question isn’t a matter of action but a matter of omission. When someone (typically a patient) asks if the surgery was a complete removal of the disease, what they’re really asking is, “will it recur?” “will I have to go through its pain again?” “will I be pulled out of my regular life as frequently as before?”

A surgery, in essence is only complete when the answer to everything above is no. Regardless of how complicated or simple your intra-op actions might’ve been, the ultimate, and most important goal, is recurrence reduction; of pathology and symptoms.

Delivering to the patient, a quality of life they once had is the paramount goal of surgery and everything else we do is in service to that goal.

Ruffling through some research papers can very quickly help even the novice amongst us understand that while surgical skill is difficult to acquire, we barely get past the basecamp in climbing the summit that is endometriosis. That is also precisely why B. Rizk et. al. report in their paper titled Recurrence of endometriosis after hysterectomy

The recurrence of endometriosis symptoms and pelvic pain are directly correlated to the surgical precision and removal of peritoneal and deeply infiltrated disease. Surgical effort should always aim to eradicate the endometriotic lesions completely to keep the risk of recurrence as low as possible.

A major challenge may lie in the visual diagnosis of endometriosis. It has been estimated that two-thirds of patients have some visual disease that many clinicians have not been trained to recognize, and this may be the only manifestation of disease (Redwine, 1990). Some lesions may appear atypically or non-pigmented (Martin et al., 1989a; Jansen and Russell, 1986). Deep endometriotic lesions located in the subperitoneal space may go completely unrecognized or be particularly difficult to visualize during laparoscopy or to access during surgery. Additionally, lesions can be hidden by peritoneal adhesions of the pouch of Douglas (Kinkel et al., 1999).

The peritoneum can be likened to a thick forest that endometriotic nodules can stealthily disappear into. In our last edition we shed light on how MRIs, when performed properly, can help discover deep infiltration but with the exception of a peritoneal inclusion cyst, these particular nodules can be very hard to find.

This means you only see peritoneal involvement when you see it. And that’s when you must decide what you should do.

There broadly exist two situations. One is of limited or localised peritoneal involvement, where nodules are observed only in one restricted region of the peritoneum, and the other is of pervasive involvement, where multiple nodules can be observed across the entire peritoneum.

While localised treatment of peritoneal nodules has been the norm, a crucial aspect has often been overlooked in the years past.

The Peritoneal Expressway

Owing to its pervasive nature, the peritoneum is this sort of highway for the disease to spread in endometriosis. Thin tissues, homogeneity in composition, the existence of folds, and abundant blood supply all make this organ ripe for endometrial growth.

Even a small number of unnoticeable cells left behind post-op can cause major recurrence.

It’s easy to appreciate why the peritoneum is difficult to dissect. Anatomy lies right below the peritoneum and examining the full extent of a single nodule while attempting to dissect is risky and notoriously difficult.

When multiple nodules rest side by side on the peritoneum, the same act of excision gets harder. And in proximity to organs like the ureter, the risk multiplies very fast.

A Surgical Strike with a Carpet Bomb

Pardon the wordplay, this writer is tired and out of creative juices.

Once you know that large sections of the peritoneum are involved, the best course of action is to remove the entire peritoneum and at Mayflower, we’ve spent a long time figuring out how to do it.

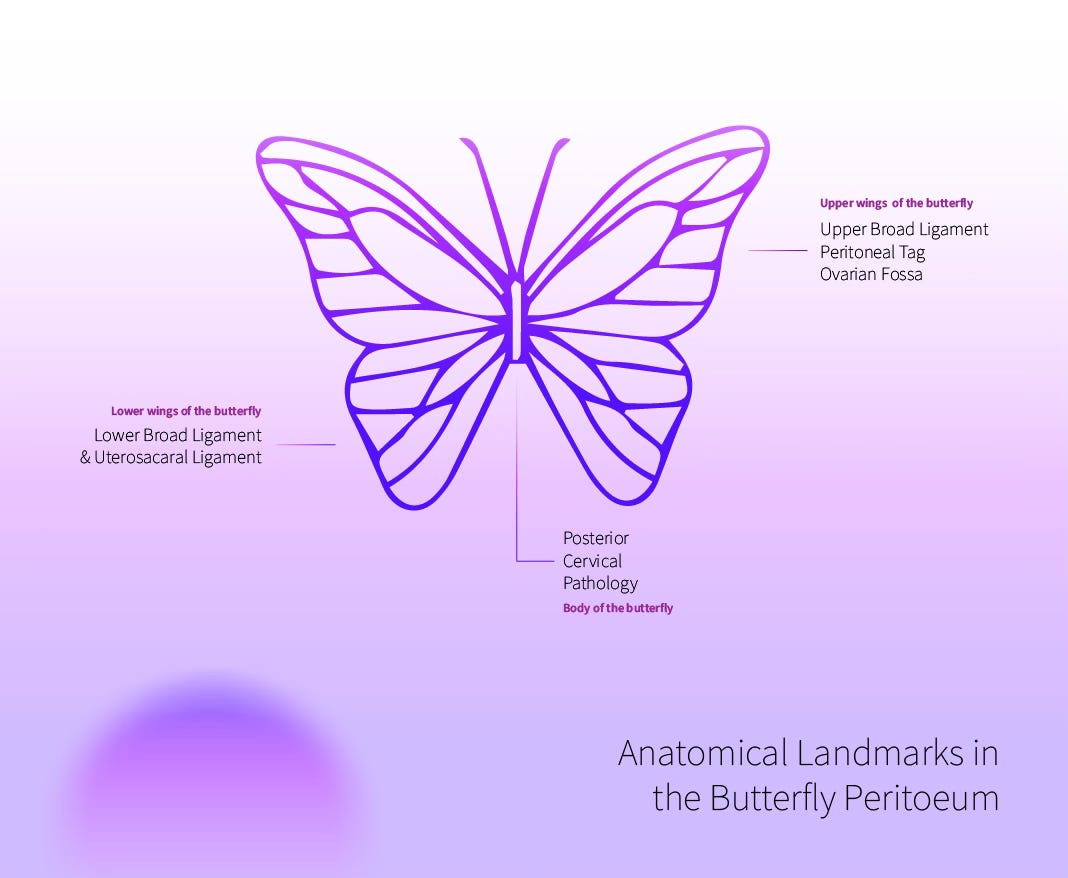

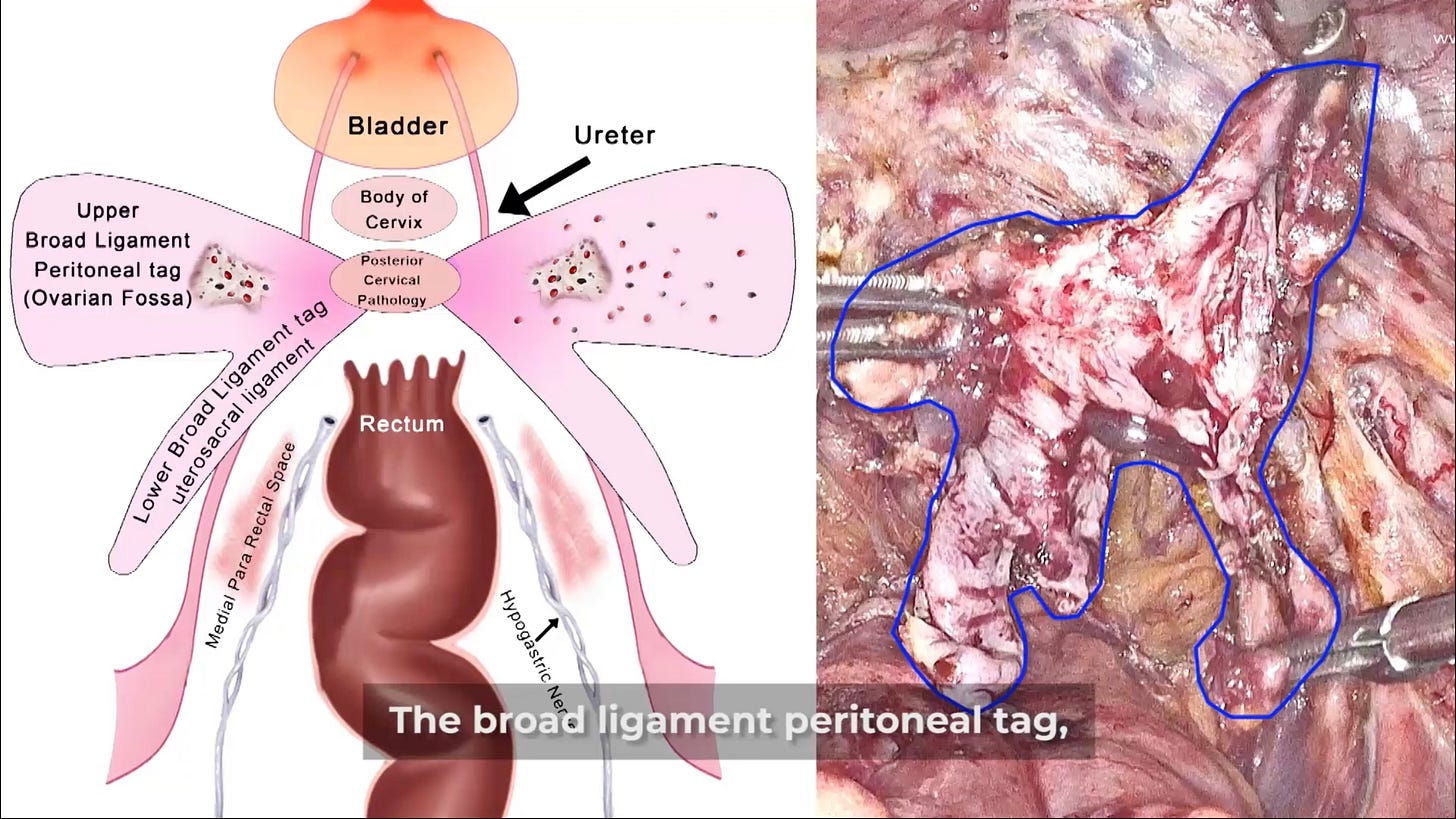

For starters, the entire peritoneum, starting from the broad ligament on the top, going through the posterior cervix to end with the uterosacaral ligament at the bottom forms a shape that resembles a butterfly.

In 2009, we finally figured how we could excise the peritoneum en-bloc. It’s what we call the Mayflower Butterfly Peritonectomy. A procedure that played a huge role in helping us reduce the recurrence rate of deep infiltrating endometriosis to a little less than 2%.

Amongst all the strides that we’ve made in recurrence reducing procedures, this has to be amongst the most important.

It does require a certain surgical tenacity but one can broadly break down the Mayflower Butterfly Peritonectomy into 4 steps

Uretrolysis

Media Pararectal Space Dissection with nerve sparing

Upper wing dissection

En-bloc removal

Let’s dive right into each of these

Uretrolysis

Even in a case of deep infiltrating endometriosis, there could be varying degrees of involvement of the ureter. We happen to have a detailed break down of the 9 levels of ureteric dissection but that’s for another day.

To begin with, owing to the nature of the ureter, disease growth doesn’t invade into it as much as it encircles the ureter often leading to stricturing and hydro nephrosis. Terrible as that is for patients who get diagnosed late, this gives us a very interesting insight into how we could dissect the disease.

The first thing to remember is that growth over the ureter will be in concentric layers. So we go up to the brim of the pelvis, place a knick and then start dissecting upwards all the way to the other end.

If there’s an obstruction in the middle, remember, it’s just another layer. Go back to a virgin area, tease, cut, and proceed.

If you do this slowly, diligently, and with focus, that disease tissue has no chance. Remember that there’s no award for finishing the surgery early. Dissect fibre by fibre till you eventually reach the mesentery of the ureter and you’re good to go.

Pro Tip:

Always provide traction laterally, and only use the tip of an ultrasonic scalpel to dissect while pulling it upwards. This will give you minimum chances of injury to the underlying Ureter

Medial Pararectal Space Dissection and a Spared Nerve

The medial para-rectal space is a created space. In that sense it is an imaginary spot that doesn’t exist but is created through surgery by dissecting the peritoneum all the way up to the denonvilliers fascia.

It is possible that a peritoneum that seems only mildly involved at first, has major fibrotic sites underneath. This is why careful and meticulous dissection is extremely important.

The other major reason you want to be careful is to spare the hypogastric nerve. Arising from the superior ganglion situated on the sacral promontory, the HGN usually runs medial and slightly below the ureter.

Saving it is easy, however if you damage it, regeneration happens at the rate of 1 millimetre per week resulting in a long tail post operative recovery period and an even longer rehab duration.

Pro Tip: Fat belongs to the organ, not the disease. While dissecting around the rectum, it helps to dissect at the upper margin of the layer of fat. This ensures we are as far away from the rectum as possible.

Once you’ve explored this space and reached the denonvillers facia from either side, this step is done. Next you move the the upper wings of the butterfly

Upper Wing Dissection

The posterior broad ligament along with the peritoneal tag (ovarian fossa) on either side forms the upper wings of the butterfly. This is often where the disease is involved deeply and superficial peritoneal excision would leave us open to the chance of missing critical instances of growth below the ovary.

While the dissection is straight forward, it helps when over a period of time, surgeons can build a sense of organ <> peritoneum margin that helps them navigate effectively around this area. Dense with several other structures, this dissection can involve a fair bit of meandering.

En-Bloc Removal

The last step of the process is an en-bloc removal of the peritoneum.

With this, you’ve removed the weeds. Your field is clear. All you really need to do next is perform the harder but more obvious and visually confirmed procedures that will further help restore a disease free anatomy, reduce symptoms, and eventually give the patient a pain free life.

This procedure has helped us with an observed recurrence rate of less than 2% and we have a strong conviction that inputs and innovations by surgeons from across the globe will only make it better.

That’s it from us this week. It’s over to you now! Share this with your friends and colleagues, send us any thoughts that you might have, we are always open to inputs.

Until next week 👋🏻

![[video-to-gif output image] [video-to-gif output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9c271af3-d6fa-40be-8b94-4d68b21a658a_600x340.gif)

![Screen Recording 2023-09-27 at 1.04.32 PM.mov [video-to-gif output image] Screen Recording 2023-09-27 at 1.04.32 PM.mov [video-to-gif output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F331b609e-f755-4e36-91c5-9ab11ee8609b_600x340.gif)

Very meticulous description of an intrinsic dissection in such a simple manner, itself depicts the depth of knowledge that Sanjay sir and Dr Smith has developed in pelvic anatomy. Kudos to team Mayflower.

This article explains intricate steps of endometriosis surgery in a simple and lucid manner . It would benefit many many gynaecologists like me