Cystectomy - The Mathematics of DIE Surgeries - Ep 3

Chocolate cysts are at the cusp common. For people who have endometriosis, chances that they will have a chocolatey cyst are relatively high when you compare it with other aspects. Some studies suggest chocolate cysts or endometriomas can be found in as high as 44% patients with endometriosis and as low as 17%, those are numbers between one in 5 and one in 2 patients. Which is, a lot.

It’s surprising then that despite their common occurrence, there is little in common in how different surgeons deal with them. Which is why today’s edition is dedicated to the process of cystectomy or the removal of endometriomas in both radicle as well as conservative surgeries.

We will continue to use our framework of the mathematics of DIE and break down the procedure into its constituents of aim, method, wisdom, risk and excellence, and explore those aspects in detail.

Let’s begin!

In the process of surgery, cystectomy comes right after colon mobilisation and uretrolysis. This creates space for dissection and at the same time, offers us an opportunity to begin removing parts of the disease that is closet to the point of occurrence.

In cases where retrograde menstruation holds true (and we don’t know for sure) the ovary and its surrounding is often the first victim of the disease, closely followed by the retroperitoneal and recto-vaginal facia.

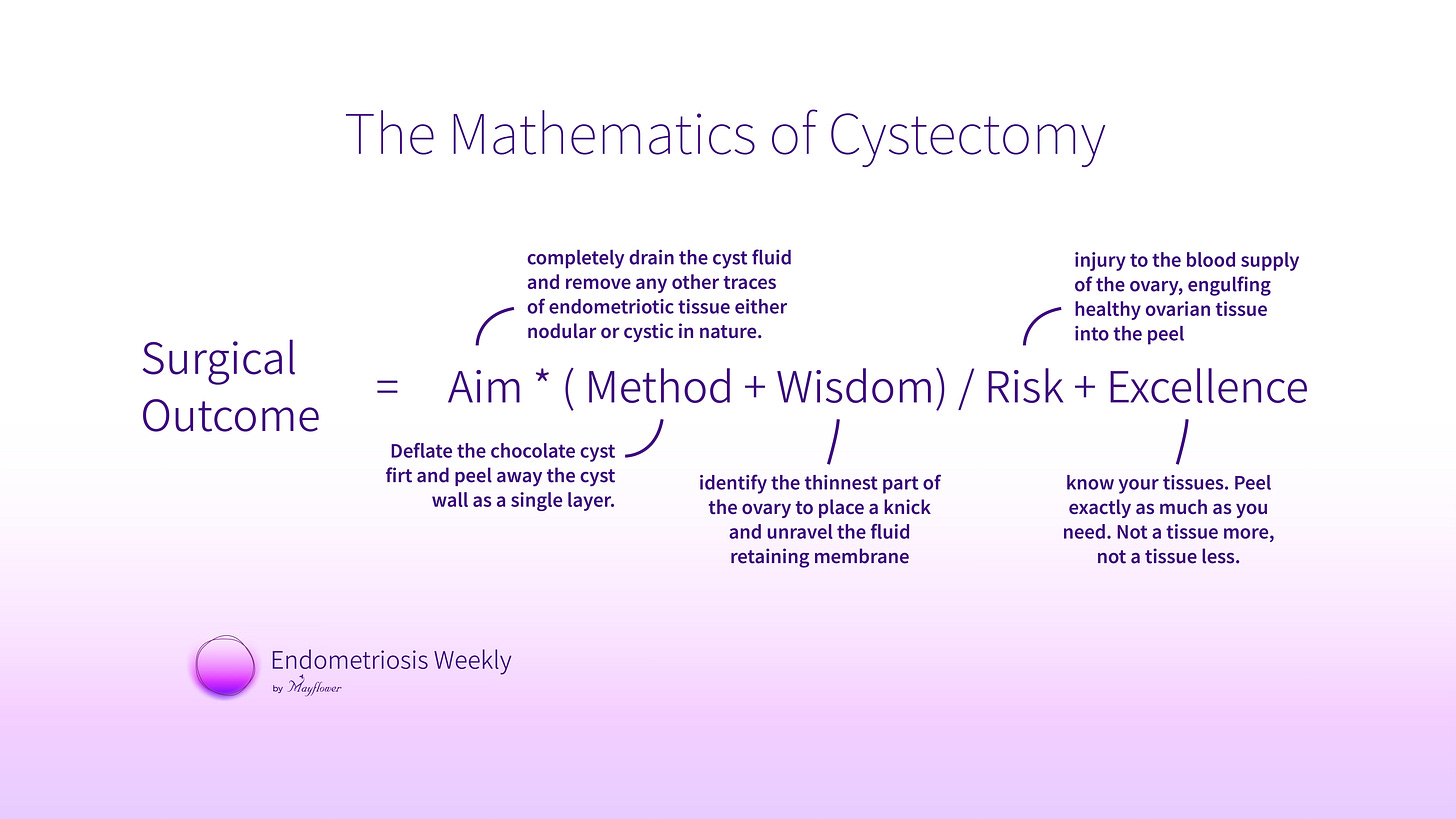

The aim here is to remove the chocolate cyst and preserve the healthy cortex of the ovary. These are cases where fertility has to be preserved or the patient simply wishes to retain their ovaries for other reasons.

Conservative surgeries are tricky since they put limitations on our ability to completely remove the disease, making the surgery more critical than a radicle case.

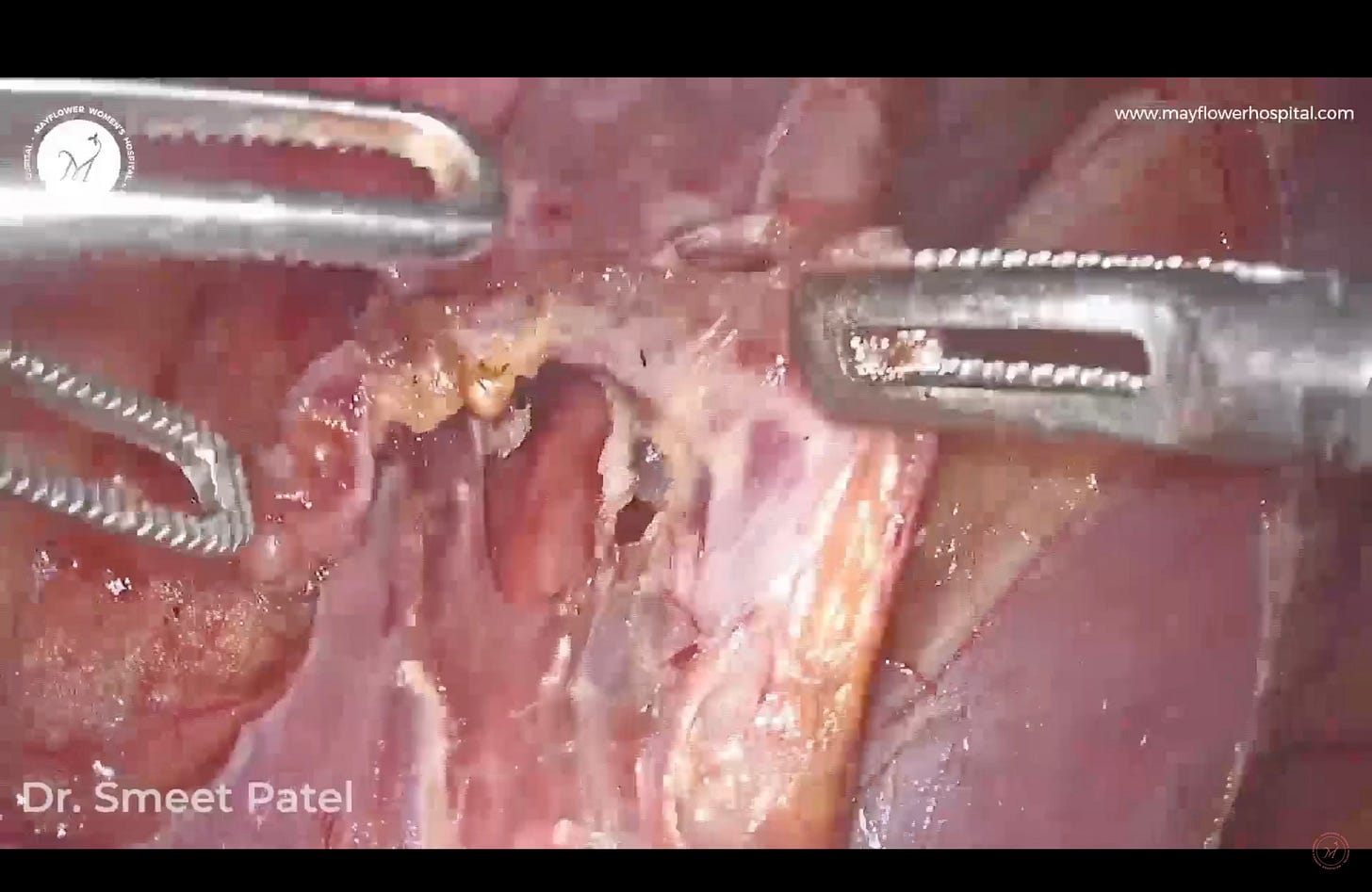

The method is to first remove all adhesions circumferentially from the ovary. Then pick the thinnest part of the ovary, place a knick, and find the two layers. One being the cyst and the other, the heathy ovarian cortex. Now apply traction and counter traction to the cyst on either sides of the knick and peel it off.

If all goes well and you don’t rupture any vasculature around the base of the ovary, you’ll have a beautiful outcome and a well managed cystectomy.

In cystectomy in recent times we plan to remove the entire cyst enmass : proper traction and counter traction, and fiber by fiber dissection. Something similar to what we try to achieve in dermoid removal; with some minor differences of course.

Excellence in this step is achieved when we can extract the complete wall of the cyst as a single mass. The biggest benefit of this is giving us a complete and clean removal of diseased tissue from the wall of the ovary. More important, we would argue, is the act of differentiating between the tissue of the cyst wall and the surface of the ovary. A clear differentiation helps us avoid unnecessary bleeding from the supply to the ovary, especially on the underside of the ovary.

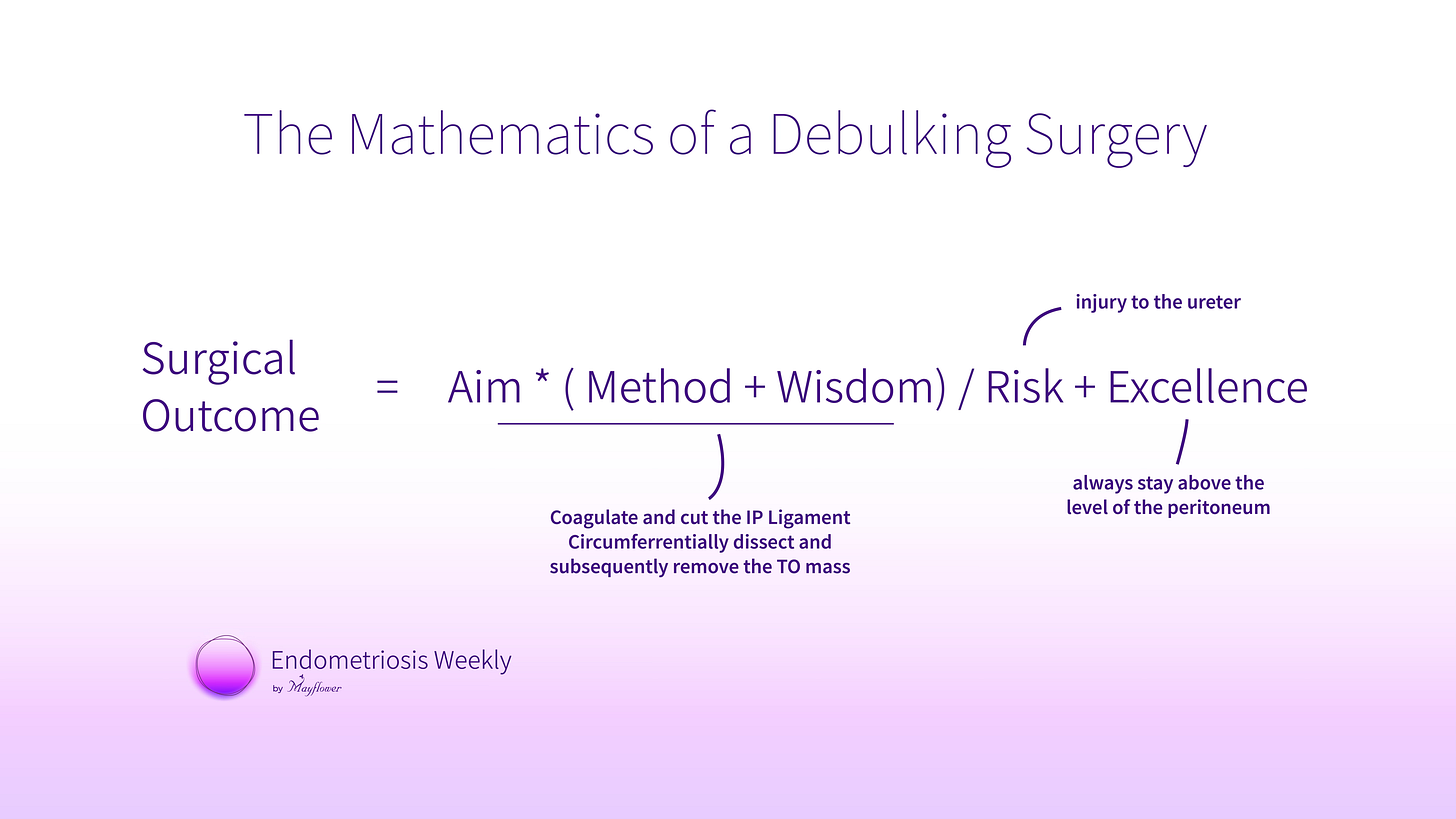

On the other hand we have radicle surgeries that work a little differently. Here we perform a complete Tubo-Ovarian Mass Removal. These cases typically also see a TLH take place.

Here, we first begin by cutting and coagulating the uterine artery at origin. The method follows first lifting the peritoneum at the base of the pelvis and making a knick.

Cranially it is dissected parallel to the IP ligament and cordally till the round ligament. The risk as you might already have guessed is that even the slightest injury to any of the vessels around could cause torrential haemorrhage.

Debulking surgery or the removal of the TO mass begins right after we have performed a complete uretrolysis, subsequently creating a window between the IP ligament and the ureter. A window that will help us perform a clean coagulation and cut on the IP ligament.

Now the complete TO mass is circumferentially dissected and subsequently removed, debulking and giving us comfortable room for further dissection.

That’s it for this week. Next week we cover the glorious case of the medial pararectal space dissection. See you soon!